Abstract

Object: This paper aims to investigate entrepreneurial motivations of various categories of rural tourism entrepreneurs, particularly highlighting the differences between Opportunity, Necessity, and Irrational entrepreneurs with a deep focus on commercial, social, irrational, as well as mixed intrinsic motives in start-up initiatives.

Methods: This research adopts the qualitative research method. 25 rural tourism entrepreneurs in Central Asia were studied in-depth, using a purposive sampling strategy.

Findings: The research revealed a specific category of rural tourism entrepreneurs defined as Irrational Entrepreneurs, which not connect their initiative and activities with an opportunity to gain philanthropic benefits. Irrational Entrepreneurs are characterized by an extremely social dominance degree in their business motivations.

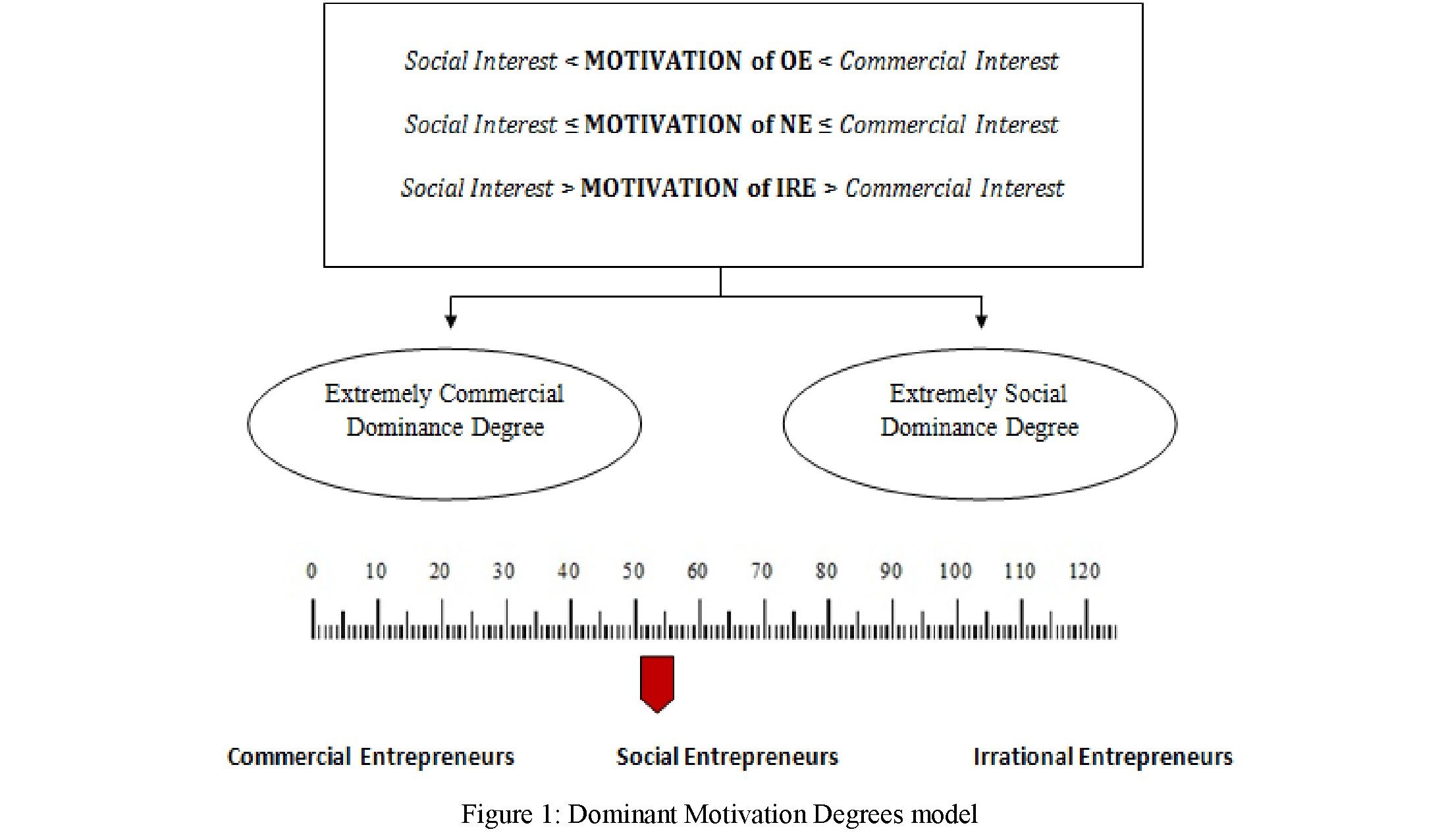

Conclusions: For contributing to the conceptual theory building, the “Dominant Motivation Degrees” model is suggested. The model indicates the impact of social and commercial components of intrinsic motives on an integral nature of entrepreneurial motivations.

Despite the fact of the past few decades of studies, entrepreneurial motivation has not yet been sufficiently considered through the prism of a typology of entrepreneurs (Hockerts, 2017; Naffziger et al., 1994; Packard, 2017). An overview of prior research shows that the distinctive features of motivations of specific categories of rural entrepreneurs are remaining under-researched and have not been comparatively analyzed (Fried, 2003; Misra & Kumar, 2000). In particular, this issue has not been appropriately investigated within the rural hospitality and tourism context (Mehdi, 2017; Sharmina et al., 2010). In the business and management literature, “entrepreneurship” is known as a well-studied phenomenon. Various aspects of an entrepreneurial process, including opportunity identification (Peiris, Akoorie & Sinha, 2013; Shepherd & DeTienne, 2005; Smith, Matthews & Schenkel, 2009) and exploitation (Plummer, Haymie & Godesiabois, 2007; Ucbasaran, Westhead & Wright, 2008) risk-taking, information search, innovativeness (Hjalager, 2010; Ndubisi & Iftikhar, 2012; Swami & Porwal, 2005), motivation (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011; Mathews, 2008) and intention (Bird, 1988; Ferreira et al., 2012; Gurel, Altinay & Daniele, 2010; Kobia & Sikalieh, 2009; Mazzarol et al., 1999) have been comprehensively discussed by a significant number of conceptual and methodological studies. A majority of research works have reflected monetary motivations of a commercial type of entrepreneurs that is widely discussed from economic, social, management, and entrepreneurship theories perspectives. There is general agreement that the limited research attention is devoted to social entrepreneurship motivations (Austin, Stevenson & Wei-Skillern, 2006; Yitshaki & Kropp, 2016), particularly with regard to the field of tourism and hospitality studies (Mottiar, 2016). However, there is a lack of research on how do motivational dimensions vary across specific typologies of rural tourism entrepreneurs. Therefore, in this paper, we argue that opportunity entrepreneurs (OE), necessity entrepreneurs (NE) and irrational entrepreneurs (IRE), identified by the research findings as specific categories of rural tourism providers, have different motivations with different dominance degrees. In this regard, this qualitative exploratory paper aims to answer the following research questions:

What are the main motivating dimensions for rural tourism and hospitality entrepreneurs?

How the motivation of IRE differs in nature from commercial and social motivations?

*Responsible author:

E-mail address: ainur88ainur@gmail

How do motivations of OE, NE, and IRE differ from each other in a dominance degree in social, commercial and mixed interest orientations?

Generally, this study aims to contribute in several ways. First, this research extends existing theories on entrepreneurial motivations and fulfils a current gap in rural tourism and hospitality context, deeply focusing on differences between three types of rural tourism entrepreneurs. Second, we have formulated research questions, which may contribute to conceptual theory building through a suggested “Dominant Motivation Degrees” model.

Theoretical Insights into Entrepreneurial Motivations

Entrepreneurial motivation is a complex phenomenon tied to cognitive behavioristic processes influencing entrepreneurial actions. The nature of motivation is usually understood by the term “entrepreneurial driving forces” implying push and pull factors (Ahunov & Yusupov, 2017; Mathews, 2008; Javalgi & Grossman, 2016). A classical approach to study motivations suggests the “goal-setting theory”, “drive theory”, and “incentive theory”, which have been applied in motivation research as basic research concepts explaining key considerations and components of intrinsic and extrinsic motives (Olomi, 2001; Shane et al., 2003). To realize a goal, one’s effort should shift from an inactive intention to active actions, where motivations become a bridge accelerating this passage (Yitshaki & Kropp, 2016). The goal is a clear representation of the perceived future plans and it makes accurate an abstract nature of motivations, drawing a distinct direction towards the targeted achievement. Mathews (2008, p.24) argued that “goal-directed behaviours are essentially grounded at the combinatorial function of individual tendencies, economic interests, value creation, and the feasibility of goal realization indicated by the environment”. Entrepreneurs may have different goals depending on individual motivations, which may vary in nature and degree. Moreover, motivation is affected by internal and external stimuli reflected by drive and incentive theories, respectively (Amabile, 1997; Srivastava, 2001). According to the interpretation given in the drive theory motivations are influenced by internal stimulus primarily associated with the physical strain (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). In this case, motivation is defined as intrinsic. This stimulus is in line with bottom-line physiological needs of Maslow’s theory of human motivation. For instance, motivations of NE operating in rural settings in many cases are driven by indigence. This category of entrepreneurs considers even a simple form of business activity as the only source of income at least non-permanent earnings. Incentive theory, in contrast, describes extrinsically motivated behavior of an individual originating from external factors and the desire to perform reinforced by a search for rewards underpins this motivation. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are not necessarily present in an individual behavior solely. In most cases they can manifest simultaneously (Cardon et al., 2017; Renko & Freeman, 2017; Shane et al., 2003). For example, in the sector of rural tourism, NE with a dominated social motive along with the desire to solve a certain social problem may also be engaged in maximization of economic gains (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). In the same manner, OE with a strongly pronounced commercial motivation may implement socially responsible practices promoting a social value within the community or region.

There are two types of factors influencing entrepreneurial motivation, which are categorized in the literature as push and pull factors. Push factors are viewed as a set of circumstances forcing people to start business ventures (Ahmad& Khan, 2014) Respondents classified as NE indicated that they have been motivated by a necessity to earn a living. These are different kinds of situations, which motivate an individual to walk away from a current job, such as the loss of employment or frustration with the present working conditions. As it was indicted by Yitshaki and Kropp (2016), entrepreneurs driven by a push motivation factor are characterized by a less competitive background and often have weak competencies in terms of education, professional experience, personal capabilities, and skills. A considerable part of rural tourism providers that have been interviewed in this research falls into the above-mentioned category. Pull factors imply internal inducement originating from a personal intention that motivates people to exploit new opportunities. It is obvious that OE with a dominant commercial motive mainly motivated by financial and business interests, focusing on achievements, self-actualization, and success. Nevertheless, social entrepreneurs may also perform under the influence of pull factors and these factors are linked to the problems in the present or past or connected to ideological motivations (Yitshaki & Kropp, 2016). According to the results of the study, rural entrepreneurs with a dominated social orientation were driven by strong humanistic, patriotic feelings and perceive their business as a part of patriotic duties. However, Mottiar (2016, p.1139), relying on Peattie and Morley (2008), states that “social enterprises as hybrids which can have a variety of mixes of motives between commercial and philanthropic”. Prior research also supports this fact and highlights that in reality social entrepreneurs similar to commercial entrepreneurs compete for philanthropic resources in a form of grants, donations or government support (Austin, Stevenson & Wei-Skillern, 2006; Chandra 2017).

Considering theoretical discussions of prior research works, further we propose that currently existing concepts as “commercial entrepreneurs” and “social entrepreneurs” cannot explain clearly all aspects of entrepreneurial motivation because our results have revealed a contradictory category of the rural tourism entrepreneur with a purely non-monetary motivation that we defined as “Irrational Entrepreneurs (IRE)”. Moreover, the dominance degree of non-monetary motivations of IRE significantly exceeds the degree of non-monetary motivations of social entrepreneurs. Therefore, we suggest measuring motivations between 3 types of rural tourism entrepreneurs by the proposed “Dominant Motivation Degrees” model (Figure 1).

Rural Tourism Business

Rural tourism is considered a business activity conducted in the countryside and organized based on unique elements of rurality, represented by the virgin natural environment, beautiful landscape, local culture, heritage, and community (Carson & Carson, 2017; Fotiadis et al., 2016; Gao & Wu, 2017). Rural tourism entrepreneurship is represented by small-scale firms and family-owned business ventures and is distinguished by a consumer-oriented approach, owing to its experiential nature. Rural tourism includes varieties of offerings organized in rural settings. These services are usually transformed into memorable consumer experiences supporting customer involvement in rural or agricultural activities. Practically, rural tourism services are organized as a B&B package which is accompanied by experiences enabling consumers to dip into rural lifestyle, to be in close contact with nature, and directly to be involved in rural activities, such as pick- your-own, animal feeding, handy works, and participation in the production process of agricultural goods (Kenebayeva, 2014). Nowadays, the Kazakh rural tourism market is represented by farm stays, agritourism offerings, rural guesthouses, and small ethnic villages.

The process of industrialization caused the shifts in socio-economic conditions of rural areas. The mass movement of people from rural areas to cities led to the growing number of holidays and vacations in remote villages. These changes have gone with other factors, such as shortening the length of holidays leading to the growing demand for short-distance rural vacations. Due to this fact, the tendency of spending holidays in the countryside has been growing quickly during the last decades. Especially, the global market is experiencing increasing demand in the family segment. The latest trends are introduced by the rising interest in environmentally friendly recreations and pursuit of authenticity (Frisvoll, 2012; Li et al., 2016; Rasoolimaneshet al.

2017; Rid et al., 2014). Such kind of new trend had a positive and progressive effect on rural areas due to business opportunities that local people might exploit.

This study adopts a qualitative research method, as it intends to provide possibilities of answering specific research questions in a more realistic manner that cannot be answered by quantitative research, in which numerical data and statistical analysis are often used (Yin 1994, Miles & Huberman, 1994). It also provides wider and more flexible channels for conducting data collection, performing subsequent analyses, and interpreting collected data (Ghauri, 2004). The qualitative method allows us to gain a holistic view of the phenomena under investigation (Bogdan & Taylor, 1975; Cassell & Symon, 1994).

A purposive sampling strategy (Patton, 1980) was used to reach the goal of our research that is to explore different motivations with different dominance degrees of opportunity entrepreneurs (OE), necessity entrepreneurs (NE), and irrational entrepreneurs (IRE), and contribute to conceptual theory building through a suggested “Dominant Motivation Degrees” model.

To gain in-depth knowledge, the case study method was applied in this paper, considering its usefulness for international business and entrepreneurship research (Piekkari et al., 2009; Vissak, 2010; Welch et al., 2011). It is suitable for explaining “how” and “why” questions, which give researchers possibilities to combine existing, developed theories with new empirical evidences (Yin, 1994). Considering the various types of entrepreneurship in the rural tourism context, such a research approach is especially appropriate for new topic areas, and it allows researchers to identify novel, testable and empirically valid theoretical and empirical insights (Voss et al., 2002). To avoid the risk of misjudging a single situation, authors chose the multi-case study approach (Ghauri, 2004) to conduct cross-case analysis and comparisons (Chetty, 1996; Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Although case studies may reduce the generalizability of the end results and contain a risk of increased observer bias (Voss et al., 2002), it is still a relevant method that allows retaining the depth of the study and richness of findings (Piekkari et al., 2009).

To follow Mason’s suggestion, “reliability”, “validity”, and “generalizability” are different measures of the quality, rigour and wider potential of research, which are achieved according to certain methodological and disciplinary conventions and principles (Mason, 1996, p. 21). Thus, authors ensure the respondent’s validation. Authors also ensure that multi-case data collected meets the criteria of trustworthiness and authenticity (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Guba & Lincoln, 2005).

Totally 25 interviews were conducted with providers of various rural tourism offerings functioning in rural areas. The number of cases was not increased due to reaching saturation (Eisenhardt, 1989). 25 respondents were included in the sample size following the approach recommended by Creswell, suggesting five to 25 numbers of interviews for the phenomenological research (Creswell, 1998). Pilot interviews were conducted with three rural tourism entrepreneurs to test the clarity and effectiveness of interview questions and responses (Stebbins, 2001). Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes to two hours (Table 1). In-depth interviews and structured questionnaires were used for the data collection.

Table 1. Entrepreneurial background and interview information

|

Provided rural tourism offerings |

Entrepreneurship category |

Interview Hours |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

1) B&B 2) Outdoor sports |

Irrational Entrepreneur |

1 hour 15 min |

|

1) B&B 2) Birds watching |

Necessity Entrepreneur |

50 min |

|

1) B&B |

Necessity Entrepreneur |

45 min |

|

1) Accommodation |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour |

|

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

55 min |

|

1) B&B 2) Agra-sales |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour 5 min |

|

1) B&B 2) Educational (scientific) excursions |

Irrational Entrepreneur |

1 hour |

|

1) B&B |

Necessity Entrepreneur |

1 hour 10 min |

|

1) B&B |

Necessity Entrepreneur |

55 min |

|

1) B&B |

Necessity Entrepreneur |

45 min |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

50 min |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

45 min |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

55 min |

|

2) Falconry |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

40 min |

|

Necessity Entrepreneur |

1 hour |

|

1) B&B 2) Hunting tours |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

45 min |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour |

|

1) B&B |

Necessity Entrepreneur |

1 hour |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

30 min |

|

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour 20 min |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

2 hours |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour 5 min |

|

1) Food service |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour |

|

1) Accommodation |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

55 min |

|

1) B&B |

Opportunity Entrepreneur |

1 hour 15 min |

|

Note – Compiled by the authors |

||

This research followed the interview protocol in three steps. In the first part of the interview protocol, respondents were put at ease through an informal conversation with the researcher. The conversation includes an introduction of the research purpose and questions regarding respondents’ demographic information. In the second part of the interview protocol, the semi-structured interviews first gained a general picture of their backgrounds and entrepreneurial journeys. In the third part of the interview protocol, respondents were addressed with open-ended questions regarding their entrepreneurial opportunity recognition processes and motivations. Between times, the interviewer changed the order of questions to keep a smooth flow of the conversation, and skipped questions were covered. The interviewer also applied the critical incident technique (Germler & Gwinner, 2008) for gaining a fruitful data set. The interviewer encouraged interviewees to share more critical moments following the chain of conversation logic.

The interviews have been conducted with rural tourism service providers operating in rural areas, located in different regions of Kazakhstan. The interview questions were developed to understand the current situation in the rural tourism market and to identify the reasons rural entrepreneurs start and operate tourism businesses associated with rural tourism. In particular rural tourism, providers have been asked to talk about the process they have gone through in making a decision and the factors inducing them to start up their own business. On the other hand, rural tourism providers have also been asked to talk about their individual experiences and would they like to make any changes in the future or do something in a different way. In order to increase the reliability of the research, special prompts have been used. According to the method suggested by Altinay and Paraskevas, analysis of the data collected by an interview took place in two stages “familiarization with the data” and “cording, conceptualization and ordering” (Altinay & Paraskevas, 2008).

At the first stage, analysis recordings of interviews have been carefully examined in order to be familiar with the content. Consequently, emerging topics have been identified. On the other hand, transcripts of interviews have been comprehensively analyzed. Method of cording has been used in qualitative data analysis. At an initial stage of analysis, the open coding technique has been applied. During this process, the empirical data has been broken down into several categories, and distinctive features of an investigated phenomenon have been revealed.

During the analytical process, the logical diagram has been constructed in order to emphasize the relationships between categories and clarify important aspects of the phenomenon. Adhering to this procedure, categories of entrepreneurs in rural tourism have been identified and constructed. Moreover, the reasons of rural entrepreneurs for starting and operating tourism businesses associated with rural tourism have been demonstrated diagrammatically, and categories of rural tourism entrepreneurs have been defined and named as Opportunity entrepreneurs (OE), Necessity entrepreneurs (NE); and Irrational entrepreneurs (IE).

Results and Discussion

The analysis of qualitative data (Table 2) identified seven of the 25 (28 percent) rural entrepreneurs who were classified as Necessity Entrepreneurs and primarily motivated by push factors. Push factors inducing entrepreneurs to act were poverty, unemployment and the lack of adequate earnings. Majority of Necessity Entrepreneurs indicated that they were forced by difficult life circumstances to become an entrepreneur. Consequently, they were driven by a dominated commercial motivations originating from socio-economic problems. For instance, NE-1 explained: “We started business due to the deadlock. There was no a job in our village at that time. We didn’t think it will be profitable or not, we just started”. NE-2 operating a rural guesthouse also stated: “It was a pick of crisis in rural areas, there were no job opportunities. As a result of this difficult situation we decided to start business in order to survive”. Entrepreneurial motivations of Necessity Entrepreneurs are mainly characterized by a commercial dominance degree essentially describing the intention of respondents to find a source of income. 16 (64 percent) of rural tourism providers classified as Opportunity Entrepreneurs link their decisions to start business to pull factors implying opportunity recognition and exploitation. 11 out of 16 Opportunity Entrepreneurs explained that tourism was seen a feasible business opportunity. Future success, self-actualization and profit maximization were the main drivers for majority of Opportunity Entrepreneurs primarily motivated by a strongly pronounced commercial motivation. OE-1 said her motivation was based on financial opportunities. “There is an increasing demand for hospitality and tourism services, it is profitable industry. I see strong financial motivation. Financially, this business is very attractive. There are necessary conditions in Kazakhstan for the development of hospitality industry. There are good perspectives”.

Table 2.Dominating motivation degrees and major findings

|

Type of rural entrepreneurs |

Case No. |

Dominant Motivation Degrees |

Major findings |

|

Irrational Entrepreneur (IE) |

1, 7 |

Social Interest >Motivation of IRE>Commercial Interest |

Motivated by pull factors; Mainly characterized by an extremely social dominance degree in their business motivations. Willingness to invest heavily in socially important projects without any expectations about future returns. Readiness to initiate socially oriented business venture without expectations of philanthropic resources in a form of grants or government support. Majority of IEs are driven by an internal inducement originating from a personal intention that motivates them to exploit new socially oriented opportunities (for instance, altruism, a strong sense of duty, patriotism) |

|

Necessity Entrepreneur (NE) |

2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 15, 18 |

Social Interest ≤ Motivation of NE≤ Commercial Interest |

Motivated by push factors; Mainly characterized by a commercial dominance degree essentially describing the intention of respondents to find a source of income; Majority of NEs are driven by a dominated commercial motivations originating from socioeconomic problems; |

|

Opportunity Entrepreneur (OE) |

4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13,14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 |

Social Interest ≤ Motivation of OE≤ Commercial Interest |

Motivated by pull factors implying opportunity recognition and exploitation; Mainly characterized by a dominant commercial intention motivated by financial and business interests, focusing on future achievements. Majority of OEs are driven by future success, self-actualization and profit maximization. In some cases, a commercial interest is supplemented by a social motivation that is seen in varying degrees. |

|

Note – developed by the authors |

|||

However, findings revealed that, in some cases, a commercial interest is supplemented by a social motivation that is seen in varying degrees. In particular, five respondents, defined as Opportunity Entrepreneurs, besides commercial motives, indicated social motives for becoming an entrepreneur. In this regard, motivations of Opportunity Entrepreneurs coincide with motivations of social entrepreneurs, which were defined by Yitshaki and Kropp (2016) as ideological motivations connected to pull factors. According to the results these category of rural tourism, entrepreneurs were driven by the intention to revive and promote national values and ethnic culture. One of Opportunity Entrepreneurs with a mixed motivation highlighted his dominated social interests in doing business. “My motivation was not a business. I wanted to revive the art of falconry in Central Kazakhstan. I wanted to promote this antique Kazakh art to people. It was very attractive both for local people and foreigners”. On the other hand, another provider stated, “I didn’t think about money. It was just my personal interest in tourism. As very Kazakh I like serve the guests. I would like to share Kazakh hospitality with others, particularly with foreign tourists in order to promote our traditions and customs”. Furthermore, findings identified an Opportunity Entrepreneur driven by motivation with a low commercial dominance degree. This rural entrepreneur associated his initiative with hobby or lifestyle. “I am a former geologist. I understood that this business would not be a good opportunity during those days. Mainly this business related to my lifestyle and personal interests, because I like travelling, I like such kind of lifestyle”.

In the social entrepreneurship theory, entrepreneurs with any social motivations are generally considered as social entrepreneurs, while the concept of motivational dominance degrees indicating the impact of social or commercial components of intrinsic motives on an integral nature of entrepreneurial motivation remains under researched. Based on prior studies social entrepreneurs are similar to commercial entrepreneurs compete for philanthropic resources in a form of grants, donations or government support (Austin, Stevenson & Wei-Skillern, 2006). The story of a socially driven Opportunity Entrepreneur fully supports this argument. “A considerable part of our capital was gained from Grants. We have started to cooperate with international nature conservation organizations. International Funds helped me to raise my start-up capital”.

Nevertheless, our findings revealed a specific category of rural tourism entrepreneurs defined as Irrational Entrepreneurs (eight percent or two respondents) which do not connect their initiative and activities with an opportunity to gain philanthropic benefits (grants, support, social recognition, and image); therefore, we argue that the social entrepreneurship theory should be extended to fully explain the nature of entrepreneurial motivations of a specific type of entrepreneurs. Considering the results of the study, Irrational Entrepreneurs are characterized by an extremely social dominance degree in their business motivation. This specific category of rural entrepreneurs is willing to invest heavily in socially important projects without any expectations about future returns. For the sake of society they are ready to start economically unviable businesses start-ups. Readiness to initiate socially oriented business venture without expectations of philanthropic resources in a form of grants or government support is a unique characteristic of these socially motivated entrepreneurs. Irrational Entrepreneurs tend to demonstrate gratuitous behaviour that gives rise to a high level of entrepreneurial risk-taking. For example, IRE-1 explained, “In 2003 I bought an old building of a kindergarten. The building has been staying empty for seven-eight years and local administration sold it at an auction. I bought it and made a tourist centre. In terms of business it was not a good opportunity. I thought what I would do in my old ages. I just wanted to do something for my region. Finally, my initiative helped to improve rural infrastructure and the region has become more attractive for local people and tourists”. On the other hand, IRE-2 reflected, “In fact I didn’t think about business. I just connected my interest in science with hospitality and tourism. I am a former geologist, and at the beginning I just created a discussion platform at my home for foreign researchers. I started to accommodate foreign researchers investigating craters in my house, and a profit made no matter”.

By studying 25 rural tourism entrepreneurs in emerging Kazakhstan, this exploratory paper aims to investigate entrepreneurial motivations of various categories of rural tourism entrepreneurs, particularly highlighting the differences between Opportunity, Necessity, and Irrational entrepreneurs with a deep focus on commercial, social, irrational, as well as mixed intrinsic motives in start-up initiatives.

Authors may address conclusions at the exploratory stage as 1) Necessity Entrepreneurs and primarily motivated by push factors, are mainly characterized by a commercial dominance degree, essentially describing the intention of respondents to find a source of income. Most of NEs indicated they were forced by difficult life circumstances to become an entrepreneur. Consequently, they were driven by dominated commercial motivations originating from socio-economic problems. 2) Opportunity Entrepreneurs link their decisions to start a business to pull factors implying opportunity recognition, and exploitation. OEs are driven by future success, self-actualization, and profit maximization. However, in some cases, a commercial interest is supplemented by a social motivation that is seen in varying degrees. This conclusion is supported by Austin, Stevenson and Wei-Skillern (2006); Yitshaki and Kropp (2016), among others. 3) Irrational Entrepreneurs, which not connect their initiative and activities with an opportunity to gain philanthropic benefits. IEs are characterized by an extremely social dominance degree in their business motivations. IEs are willing to invest heavily in socially important projects with no expectations about future returns. For the sake of society they are ready to start economically unviable businesses start-ups. Readiness to initiate socially oriented business venture without expectations of philanthropic resources as grants or government support.

This paper contributed to the entrepreneurship literature by studying the main motivating dimensions of rural tourism and hospitality entrepreneurs. It revealed a specific category of rural tourism entrepreneurs defined as Irrational Entrepreneurs, which do not connect their initiative and activities with an opportunity to gain philanthropic benefits. The paper focuses on illustrating how do motivations of OE, NE and IRE differ from each other to a dominant degree in social, commercial and mixed interest orientations. For a better demonstration, authors also developed and proposed the “Dominant Motivation Degrees” model of which indicates the impact of social and commercial components of intrinsic motives on an integral nature of entrepreneurial motivations.

Based on the above cases, authors developed several managerial implications. Government shall provide support to various rural entrepreneurs based on the types of entrepreneurial ventures and the owners’ entrepreneurial motivations. The study provides important managerial implications for policy makers working out regional development strategies through implementing tourism stimulation projects. Local authorities should motivate rural community for entrepreneurial activity to maintain sustainable development practices.

Future research could develop in several directions. For example, it could be studied how irrational entrepreneurs will develop business initiatives further in rural area – do their motivations change through a long-term period. Researchers may also further study IEs in various industrial and business fields to discover more characteristics and behaviours. Both quantitative and qualitative data can be collected from different parts of the world to conduct comparative studies and mixed methods analyses. Furthermore, a longitudinal approach can be used to analyze IEs in a more comprehensive manner and discover the changing patterns of their entrepreneurial journeys.

References

- Ahmad, S.Z., Jabeen, F., & Khan, M. (2017). Entrepreneurs choice in business venture: Motivations for choosing home-stay accommodation businesses in Peninsular Malaysia. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 31–40.

- Ahunov, M., & Yusupov, N. (2017). Risk attitudes and entrepreneurial motivations: Evidence from transition economies. Economics Letters, 160, 7–11.

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: same, different or both? Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice,1–22.

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The case for Intention. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453.

- Bogdan, R., & Taylor, S.J. (1975). Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods. New York: John Wiley.

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial Motivations: What Do We Still Need to Know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26.

- Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (1994). Qualitative research in work contexts. C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.). Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research (pp. 1–13). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Cardon, M.S., Glauser, M., & Murnieks, C.Y. (2017). Passion for what? Expanding the domains of entrepreneurial passion. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 24–32.

- Carson, D. A., & Carson, D. B. (2017). International lifestyle immigrants and their contributions to rural tourism innovation: Experiences from Sweden’s far north. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 230–240.

- Chetty, S. (1996). The case study method for research in small- and medium-sized firms. International Small Business Journal, 15(1), 73–85.

- Chandra, Y. (2017). Social entrepreneurship as emancipatory work. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(6), 657–673.

- Denzin, N.K., & Lincoln, Y.S. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks and London: Sage. Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. Eisenhardt, K., & Graebner, M. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 25–32.

- Ferreira, J.J., Raposo, M.L., Rodrigues, R.G., Dinis, A., & do Paco, A. (2012). A model of entrepreneurial intention: An application of the psychological and behavioral approaches. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 424–440.

- Fotiadis, A., Yeh, S., &Huan, T.C. (2016). Applying configural analysis to explaining rural-tourism success recipes. Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1479–1483.

- Frisvoll, S. (2014). Power in the production of spaces transformed by rural tourism. Journal of Rural Studies, 28(4), 447–457.

- Gao, J., & Wu, B. (2017). Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tourism Management, 63, 223–233.

- Ghauri, P. (2004). Designing and conducting case studies in international business research. R. Marschan-Piekkari & C. Welch (Eds.). Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for International Business (pp. 109–124). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Gremler, D.D., & Gwinner, K.P. (2008). Rapport-building behaviors used by retail employees. Journal of Retailing, 84(3), 308–324.

- Guba, E.G., & Lincoln, Y.S. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions,and emerging confluences. N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 191–215).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gurel, E., Altinay, L., & Daniele, R. (2010). Tourism student’s entrepreneurial intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 646–669.

- Hjalager, A.M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31, 1–12.

- Javalgi, R.G., & Grossman, D.A. (2016). Aspirations and entrepreneurial motivations of middle-class consumers in emerging markets: The case of India. International Business Review, 25(3), 657–667.

- Kenebayeva, A.S. (2014). A study of consumer preferences regarding agritourism in Kazakhstan: A comparative study between urban and rural area consumers, Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 6(1), 27–39.

- Kobia, M., & Sikalieh, D. (2009).Towards a search for the meaning of entrepreneurship. Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(2),110–127.

- Li, P., Ryan, C., & Cave, Jenny. (2016). Chinese rural tourism development: Transition in the case of Qiyunshan, Anhui. – 2008–2015. Tourism Management, 55, 240–260.

- Mason, L. (1996). Qualitative Researching. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Mathews, J. (2008). Entrepreneurial process: A personalistic-cognitive platform model. VIKALPA, 33(3), 17–34.

- Mazzarol, T., Volery, T., Doss, N., & Thein, V. (1999). Factors influencing small business start-ups. A comparison with previous research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 5(2), 48–63.

- Miles, M.B., &Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. London: Sage.

- Mottiar, Z. (2016). Exploring the motivations of tourism social entrepreneurs: The role of a national tourism policy as a motivator for social entrepreneurial activity in Ireland. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(6), 1137–1154.

- Ndubisi, N.O., & Iftikhar, K. (2012). Relationship between entrepreneurship, innovation and performance. Comparing small and medium-size enterprises. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 214–236.

- Patton, M.Q. (1980). Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Packard, M.D. (2017). Where did interpretivism go in the theory of entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 536–549.

- Peiris, I., Akoorie, M., & Sinha, P. (2013). Conceptualizing the process of opportunity identification in international entrepreneurship research. South Asian Journal of Management, 20(3), 7–38.

- Piekkari, R., Welch, C., & Paavilainen, E. (2009). The case study as disciplinary convention: evidence from international business journals. Organizational Research Methods, 12 (3), 567–589.

- Plummer, L.A., Haynie, J.M., & Godesiabois, J. (2007). An essay on the origins of entrepreneurial opportunity. Small Business Economics, 28, 363–379.

- Renko, M., & Freeman, M.J. (2017). How motivation matters: Conceptual alignment of individual and opportunity as a predictor of starting up. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 56–63.

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M., Ringle, C.M., Jaafar, M., & Ramayah, T. (2017). Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tourism Management, 60, 147–158.

- Rid, W., Ezeuduji, I.O., & Haider, U.P. (2014). Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in The Gambia. Tourism Management, 40, 102–116.

- Shepherd, D.A., & DeTienne, D.R. (2005). Prior knowledge, potential financial reward, and opportunity identification. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 91–112.

- Smith, B.R., Matthews, C.H., & Schenkel, M.T. (2009). Differences in entrepreneurial opportunities: the role of tacitness and codification in opportunity identification. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(1), 38–57.

- Stebbins, R.A. (2001). Exploratory research in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.