Currently the Eurasian initiative within the space of the former Soviet Union, particularly its version of Kazakhstan, is associated with the recent integration associations of economic nature, namely the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU), the Eurasian Economic Space (EES) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

It is commonly accepted view that the starting point of the Eurasian economic integration was the speech of President Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan at Lomonosov Moscow State University in March 1994. However, Kazakhstan’s initiative had been articulated for the first time in

1991 right after the Belavezha Accords of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine had established the tripartite Commonwealth of Independent States and the USSR had been officially dissolved.

Nursultan Nazarbayev took the initiative at the meeting of the leaders of the former Soviet Republics in Alma-Ata trying to prevent the previously existing single economic, social and cultural space from complete disintegration. Thus, the Eurasian initiative of Kazakhstan has a history as long as the post-Soviet existence of the CIS countries and, therefore, is worth a more detailed consideration.

History of Eurasian Initiative: from Alma-Ata Protocol to the Eurasian Economic Union

Given that the first step towards an integra

tion within the post-Soviet space was made at the meeting of the leaders of the former Soviet Republics in Alma-Ata summoned by Nazarbayev on December 21st, 1991 and was aimed at preventing the complete disintegration after the Belavezha Accords had been signed on December 8th by the leaders of the three Soviet Republics of Belarus, Ukraine and Russia. The meeting in Alma-Ata, attended by eleven heads of former Soviet Republics, resulted in adoption of the Alma-Ata Protocol that stipulated the major provisions for establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States. These provisions were the following:

- Commonwealth shall be based on the principle of equality and its institutions shall be formed on a parity basis and operating in the manner determined by the agreement within the members of the Commonwealth, which, in turn, shall be neither a state nor a supranational entity;

- joint command of the strategic military forces and the control over the nuclear weapons shall be exercised in order to maintain international security; however, the parties shall respect each other’s decisions to achieve the status of a nuclear-free and(or) neutral state;

- membership in the Commonwealth of Independent States shall be open to all other former Soviet Union Republics as well as any state sharing the goals and principles of the Commonwealth;

- members of the Commonwealth shall reaffirm their commitment to cooperation in formation and development of a common economic space and single European and Eurasian markets [1].

The above goals make it apparent that the idea of the Eurasian economic integration for the first time appeared in Alma- Ata Protocol.

Therefore, one can maintain that the Eurasian initiative can be traced back to December 1991.

The next significant step in the development of the idea was made by President Nazarbayev at Lomonosov Moscow State University. During his speech, Nazarbayev proposed the project of a Eurasian integration that would be based on a supranational structure that he called the “Eurasian Union” because, according to Kazakhstan’s President, this would facilitate a closer and more effective economic cooperation instead of the amorphous CIS. Nazarbayev stressed that the CIS was not adequate to the realities of the contemporary world, neither did it encourage the member states to proceed further towards greater integration. The “Eurasian Union”, on the contrary, in Nazarbayev’s opinion, was exactly what the people needed [2].

Nazarbayev noted that, since the establishment of the CIS, its members - sometimes gravitating towards each other and the other time moving ever further - had signed more than 400 documents on cooperation, but almost none of them had been actually implemented [2].

Nazarbayev pointed at the need to elevate the CIS onto a qualitatively deferent level on the basis of a new interstate association formed on the principles of voluntariness and equality. Such an association, according to Kazakhstan’s President, could bear the name of the Eurasian Union. The principles, it would be based on, should differ from those of the CIS; it should create a number of supranational bodies to achieve the two key goals i.e. formation of a common economic space and maintenance of a common defense policy [2].

It is important to stress, however, that Nazarbayev did not advocate for delegating of all matters to the supranational bodies of the future union. On the contrary, he insisted that those relating to the sovereignty, domestic and foreign policy and political system should remain within the domestic affairs of the member states and the Union should be based on the principle of non-interference [2].

Later, in 2001, Nazarbayev once again reaffirmed the basic principles he thought the Eurasian Union should be established on were political sovereignty and non-interference. In his article in the “Izvestiya” newspaper, Nazarbayev made the following points. The first, he said that, although the cultural and civi

lizational factors were very important, the integration should be motivated primarily by economic pragmatism. “These are economic interests not abstract geopolitical ideas and slogans that engine integration processes” - Nazarbayev wrote. Therefore, according to Kazakhstan’s President, the future Eurasian Union should be built as a common economic space embracing our nations for the purpose of their successful economic development [3].

The second point Nazarbayev made was that the participation into the integration project should be voluntary. Each state or, to be more precise, each nation should make an independent decision and form its own understanding why to integrate. However, Nazarbayev underlined that the contemporary globalizing world was making it impossible and insensible to cherish one’s self-sufficiency and uniqueness and continue the isolationist path [3].

The third point was about the equality of the members of the Eurasian Union that Nazarbayev stressed as the vital condition if it was to succeed. The member states shall respect each other’s sovereignty and inviolability of the state borders and restrain from any interference into the domestic affairs of their fellow partners in the Union.

The nest important thing, emphasized in the article, was that the supranational bodies, Nazarbayev was talking about, should work according to the principle of consensus and should take into account the individual interests of all member states. Those bodies should be granted very well-defined and realistic powers and that kind of arrangement should, by no means, impede or limit the political sovereignty of the states concerned. Nazarbayev cited the example of the European Union as a model of successful integration [3].

In 1994, these proposition was not responded enthusiastically by the other members of the CIS. However, one should not underestimate its significance for the idea of the Eurasian integration as it has been promoted by Kazakhstan because it was the moment when the foundational principles were articulated for the first time that would lay the basis for the future integration projects.

In particular, back in 1994, the main provisions of the Eurasian economic integration were set out including both the name of the future union and the fundamentals of its functioning such as formation of a number of supranational bodies, mergence of the economic spaces while preserving the independence and political sovereignty of the member states. These are the relevant principles now, twenty years later, for the ECU and the EES and, eventually, for the EEU.

Speaking about the history of Eurasian integration, it is important to mention that there had been a number of preliminary initiatives within the CIS before the next stage the Eurasian integration began. Some of these initiatives are the following:

- on April 15th, 1994, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Ukraine signed the CIS Free Trade Zone Agreement;

- on January 20th, 1995, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia conducted the first agreement establishing the Customs Union;

- on March 29th, 1996, Belarus Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia signed the Treaty on Increased Integration in the Economic and Humanitarian Fields.

Thus, back in the mid-1990s, within the CIS, there were efforts to push for deeper integration

and one of them even resulted in the establishment of the Customs Union. However, very little was implemented; more often the agreements that, otherwise, could have made rather significant difference in terms of a genuine integration, were emasculated before even being realized.

The example of the CIS FTZ is very illustrative. The respective Agreement was signed in April 1994 shortly after Nazarbayev’s speech at Moscow State University. However, the actual multilateral free trade regime was not established. The parties, including Russia, failed to agree on the list of exemptions from the free trade regime that was to become an integral part the CIS Free Trade Zone Agreement.

For over 15 years, the efforts to revive the CIS Free Trade Zone continued with varying degrees of success. There were a number of agreements reached at the CIS summits and there were a number of programs adopted by the Commonwealth, However, this idea was not realized until October 18th, 2011, when the Heads of the Governments of the CIS states concluded a new treaty on the Free Trade Zone in St. Petersburg. Yet, the Agreement was not unanimous, only eight of the eleven CIS member states signed it*. It was when the history of CIS FTZ really began.

The example of the CIS FTZ that took almost two decades to be implemented, shows how inefficient the Commonwealth was as a fa

cilitator of economic integration. The existing framework of the CIS proved that any genuine steps towards further integration were hampered by some individual states unable to make any concessions and being reluctant in terms of establishment of any supranational bodies where they were supposed to delegate a part of their economic sovereignty.

The Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC) emerged because the CIS impotence as a facilitator of integration had become apparent to all. The EurAsEC was a milestone in the Eurasian integration process.

The Treaty establishing the EurAsEC was

1 Notably, not all the signatories have ratified the treaty so far.

signed on October 10th, 2000 in Astana and came into force on May 30th, 2001. This integration association was initially formed by the five states, namely Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan that were ready for a closer integration that would mean the establishment of supranational bodies and delegating a part of their economic sovereignty in the interest of enhanced development of all.

On January 25th, 2006, Uzbekistan signed the Protocol of Accession. In October 2008, Uzbekistan, however, suspended its membership. Since May 2002, Ukraine and Moldova had had the observer status with the EurAsEC and Armenia had been an observer since January 2003. The Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Community stipulated for establishment of the Interstate Aviation Committee (IAC) and the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB).

The EurAsEC was established to facilitate the formation of the ECU and the EES with a more general goal to deepen the integration in economic and humanitarian fields.

So far, the economic integration in Eurasia has undergone the following stages: the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), Eurasian Customs Union (ECU), Eurasian Economic Space (EES) and finally the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) that has been functioning since January 1st, 2015 with the ECU and EES being the integration structures of higher levels within the EurAsEC with full legal names “The EurAsEC Customs Union” and “The EurAsEC Common Economic Space”.

The major goals of the EurAsEC were the following:

- establishment of a full-fledged free trade regime unifying the customs tariffs and building a single system of non-tariff regulations;

- ensuring free movement of capital;

- creation of a single financial market;

- finding the common ground to formulate the principles and conditions to introduce a single currency within the EurAsEC;

- establishing of the common rules for trade and access to the domestic markets of the member states;

- establishment of a common unified system of the customs regulation;

- development and implementation of the intergovernmental programs of specific goaloriented nature;

- creation of a single market for transport services and integration of the transport systems;

- creation of a single energy market;

- ensuring equal access to the foreign investments for all member states;

- ensuring freedom of movement for the citizens of the EurAsEC member states within the Community;

- harmonization of the social policies in order to create a community of the welfare states, building a single labor market, common educational system as well as pursuing coordinated policies in terms health-care, migration and other issues;

- convergence and harmonization of the national legislations to facilitate the interaction of the legal systems of the EurAsEC member states to create a common legal space within the Community [4].

Additionally, a number of supranational institutions, namely the Eurasian Development Bank, the Anti-Crisis Fund and the Center for High Technology, were established within the EurAsEC to promote integration and enhance a united capacity to deter possible negative impact of the external factors.

In parallel with the EurAsEC, there was a side project of the Eurasian integration named the Eurasian Economic Space (EES). The first

try included the four countries, namely Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine who signed a respective treaty in September 2003. Notably, the position of Ukraine may be assessed as counter-productive; it repeatedly made unrealistic demands threatening the withdraw from the EES if they would not been met by the other member states. For example, in 2005 Ukraine put forward an unacceptable condition for its further participation the EES, namely establishment of a free trade zone without any restrictions i.e. abolition of all quotas and duties. Kiev also blocked any attempts to create supranational bodies, it refused to establish the Customs Union and to sign all the documents required. In the result of this behavior of Ukraine, the signing of the documents that would enable formation of that integration structure was delayed for almost ten years.

On December 9th, 2009, at the informal summit in Almaty, Presidents of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia approved the Action Plan for 20102011 that provided for conclusion of twenty international treaties during the next two years so that the Eurasian Economic Space would have been established by January 1st, 2012.

For the purpose of its timely realization, the development and introduction of the legal framework of the EES was scheduled for 20102011 providing for adoption and implementation of dozen agreements by July 1st, 2011 while the remaining six agreements on the EES should be signed by January 1st, 2012. Under the resolution 9 of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council, the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Space entered into force on January 1st, 2012.

The EurAsEC was being consolidated in parallel with the formation of the Eurasian Customs Union. It was the establishment of the ECU that signified a decisive step forwards the full-fledged Eurasian economic integration that, at this point, had transcended the political discourse of Kazakhstan becoming a generally accepted idea in the countries that would become the members of the future union. Since the 1990s, the Customs Union project had also undergone a series of gradual moves towards its actual realization on January 1st, 2015. These stages were the following:

- in 1999, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan signed the Treaty on the Customs Union and the Common Economic Space that stipulated the eventual transformation of the Customs Union it was establishing into the Common Economic Space [5];

- in August 2006, the leaders of the EurAsEC, at their informal summit in Sochi, reached an agreement that the efforts to create the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia, which would be possibly joined by Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, should be accelerated [5];

- abovementioned agreement reached at the summit in Sochi enabled Belarus Kazakhstan and Russia to sign the Treaty on the Eurasian Customs Union in October 2007 [5];

- in June 2009, the supreme body of the ECU scheduled the steps to build a single customs territory within the ECU setting January 1st, 2010 as the first stage of its formation [5];

- on January 1st, 2010, the customs on the border of Belarus and Russia were closed; the ECU member states introduced a unified cus

toms tariff within their territories. Since January 1st, 2011, the member states started the regime of free movement of goods and services. Finally, on July 1st, 2011, the customs were closed on the border between Kazakhstan and Russia. Thus, the process of the establishment of a single customs space of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia was complete [5];

Next, the three states started the work to form a bazed common economic space that would be on the recently established ECU. The Presidents of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia signed the Declaration on Eurasian Integration on November 18th, 2011. The date when the future Eurasian Economic Space would be launched was scheduled on January 1st, 2012. The EES, being a next stage towards deeper integration, meant free movement of goods and services, capital and labor. This was when the leaders of the three states declared that the ECU and then the EES should result in the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union [5]. On the same day, the heads of the three states signed the Agreement on Eurasian Economic Commission that would be a single standing body of the ECU and of the EES. The Commission started functioning on February 2nd, 2012 [5].

In conclusion it is important to note that during the two decades of the evolution of the Eurasian integration project from the Alma-Ata Protokol of December 21st, 1991 to its actual realization in the form of the Eurasian Economic Space of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia on January 1st, 2012, the President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev played the leading role in the process. Both Almaty and Astana hosted the events that proved to be of crucial importance of the consolidation of the Eurasian economic integration. Thus, it would not be an exaggeration to state that the economic integration within Eurasia has been a realization of the particular version of the Eurasianism (pragmatic Eurasianism) articulated for the first time by President Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan and, therefore, the Eurasian initiative per se may be attributed to Kazakhstan in terms of its origin.

Macroeconomic Dynamics within Integrated Eurasian Region: Current Trends and Preliminary Outcomes

Kazakhstan’s initiative of the Eurasian integration has always been primarily motivated by economy and aimed at intensification (sometimes resumption) of the economic cooperation in the key fields, namely trade, industry and in vestment. This economic considerations have always been of the principle importance for Kazakhstan when it made the efforts to promote a number of initiatives in order to establish certain kind of integrated structures within the Post-Soviet space. Those initiatives varied from the proposal to create the CIS that embraced the majority of the former Soviet Republics to the project of the Eurasian Union that has been functioning since January 1st, 2015.

The paper deals with the analysis of the available data to see how successful the economic integration had been since the first instances of its mere articulation until the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union. This kind of assessment is only sensible and possible in terms of those integrated structures that have been genuinely viable, namely the EurAsEC as well as the ECU and EES enabled by the EurAsEC.

Since the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Community entered into force in 2001, it appears to be sensible to consider this date as the starting point for the analysis. The results of the analysis presented in this paper, reveal the trends of the economic development of the countries involved in the process of Eurasian integration. Moreover, the analysis duplicates the stages of the Eurasian integration starting with the foundation of the EurAsEC and proceeding to the ECU/EES. Further, the paper

deals with the basic macroeconomic patterns in the five EurAsEC member states in the period from 2001 to 2010.

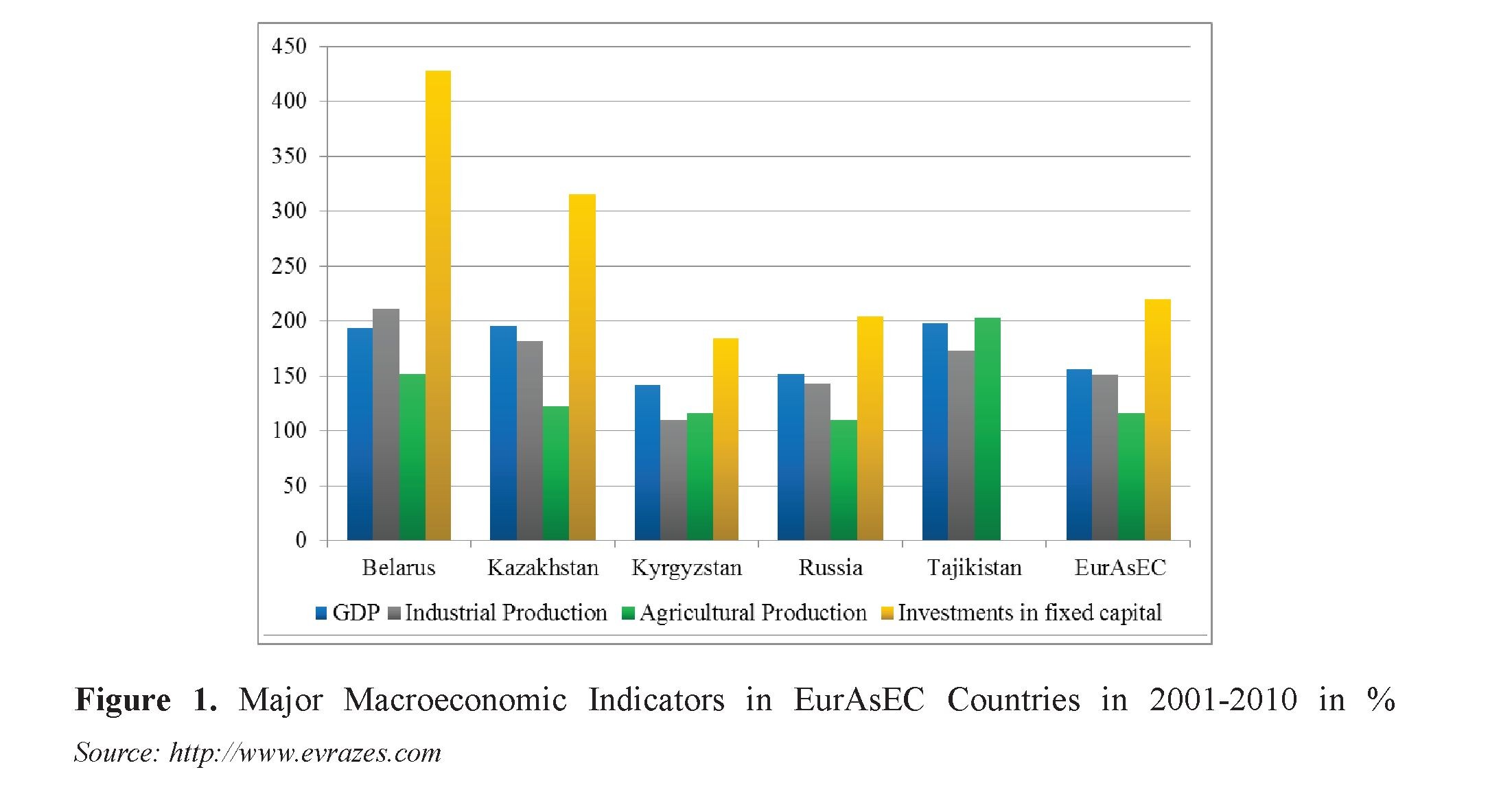

Firstly, during the ten-year period of its operation, the EurAsEC demonstrated quite a steady growth of all the key macroeconomic indicators. That growth was experienced in all the five member states and, therefore, effected the indicators of the EurAsEC as a whole (Figure 1).

The GDP, being the main macroeconomic indicator, increased in the five countries; for example the growth was 141% in Kyrgyzstan and 198% in Tajikistan. The industrial production growth rate differed from the minimum twofold increase in Kyrgyzstan to the maximum threefold rise in Belarus. It is very important to note that the most rapid growth was in the investment into the fixed capital that provided the foundation for future economic growth. Those indicators grew in the all five countries of the Eurasian Economic Community from the minimum 184% in Kyrgyzstan to the maximum 428% in Belarus.

However, the qualitative analysis of the EurAsEC macroeconomic indicators as such is not suffice. The background global trends should be taken in account as well. This would enable to make a more grounded conclusions about the processes in the Eurasian Economic Community and to assess whether the macroeconomic performance can be estimated as good and, more importantly, whether the causes of the growth originated elsewhere rather than in the fact of the economic integration per se.

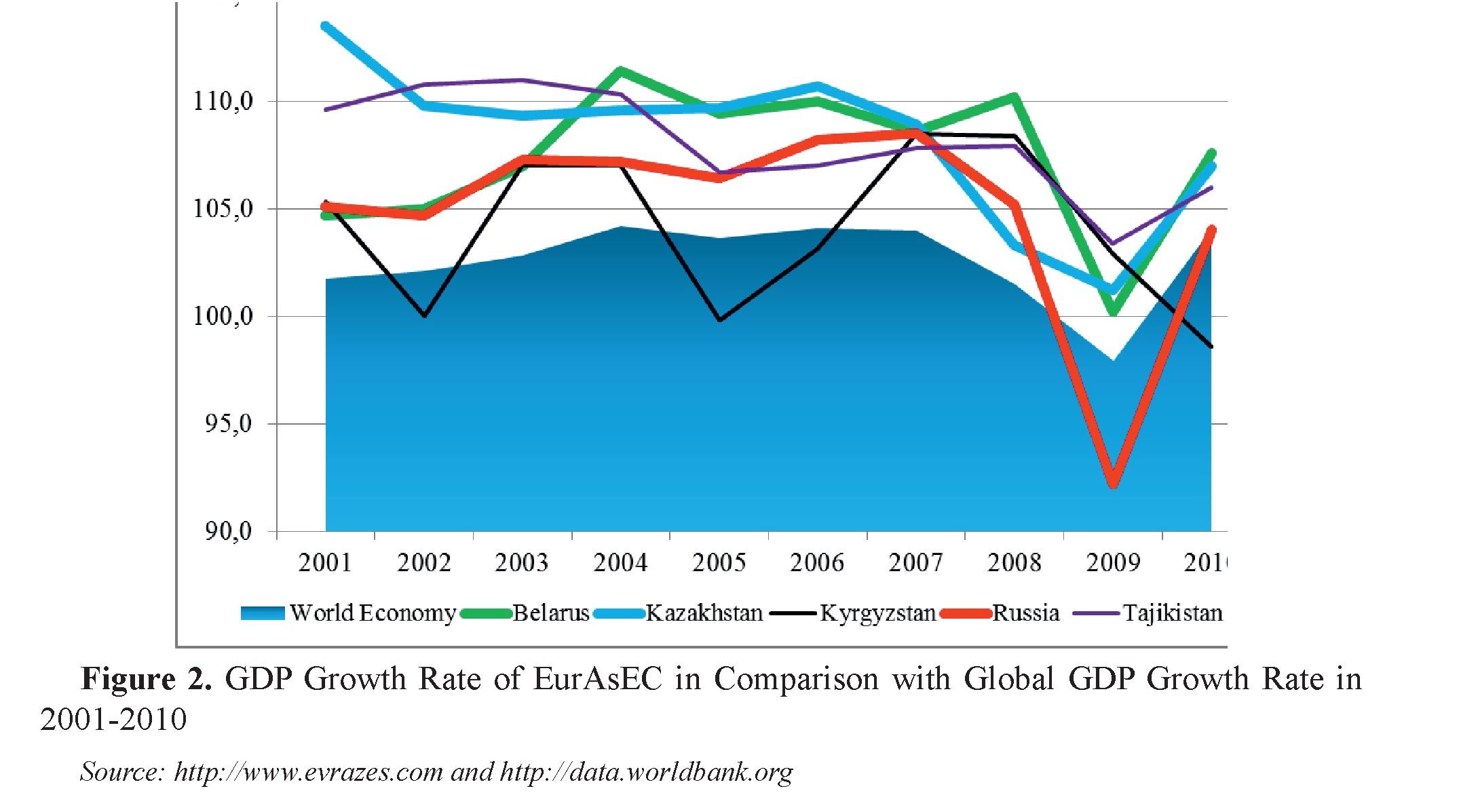

If one compares the GDP growth rate during 2001-2010 throughout the EurAsEC with the global GDP growth rates in the same period, it is apparent that the EurAsEC growth indicators were much higher than the world average ones (Figure 2).

The GDP growth exceeded the world average in the majority of the EurAsEC member states during the pre-crisis period. While the average growth of the world economy in 2001-2008 amounted to 3%, that figure measured 9.4% in Kazakhstan, 8.9% in Tajikistan, 8.3% in Belarus, 6.6% in Russia and 4.9% in Kyrgyzstan respectively. Despite the crisis of 2009, in 2010 the economies of the EurAsEC came up to the world average in terms of the GDP growth.

Moreover, the overall growth during the decade was significantly higher both in the individual members of the EurAsEC and in the Community as a whole than that of the world average.

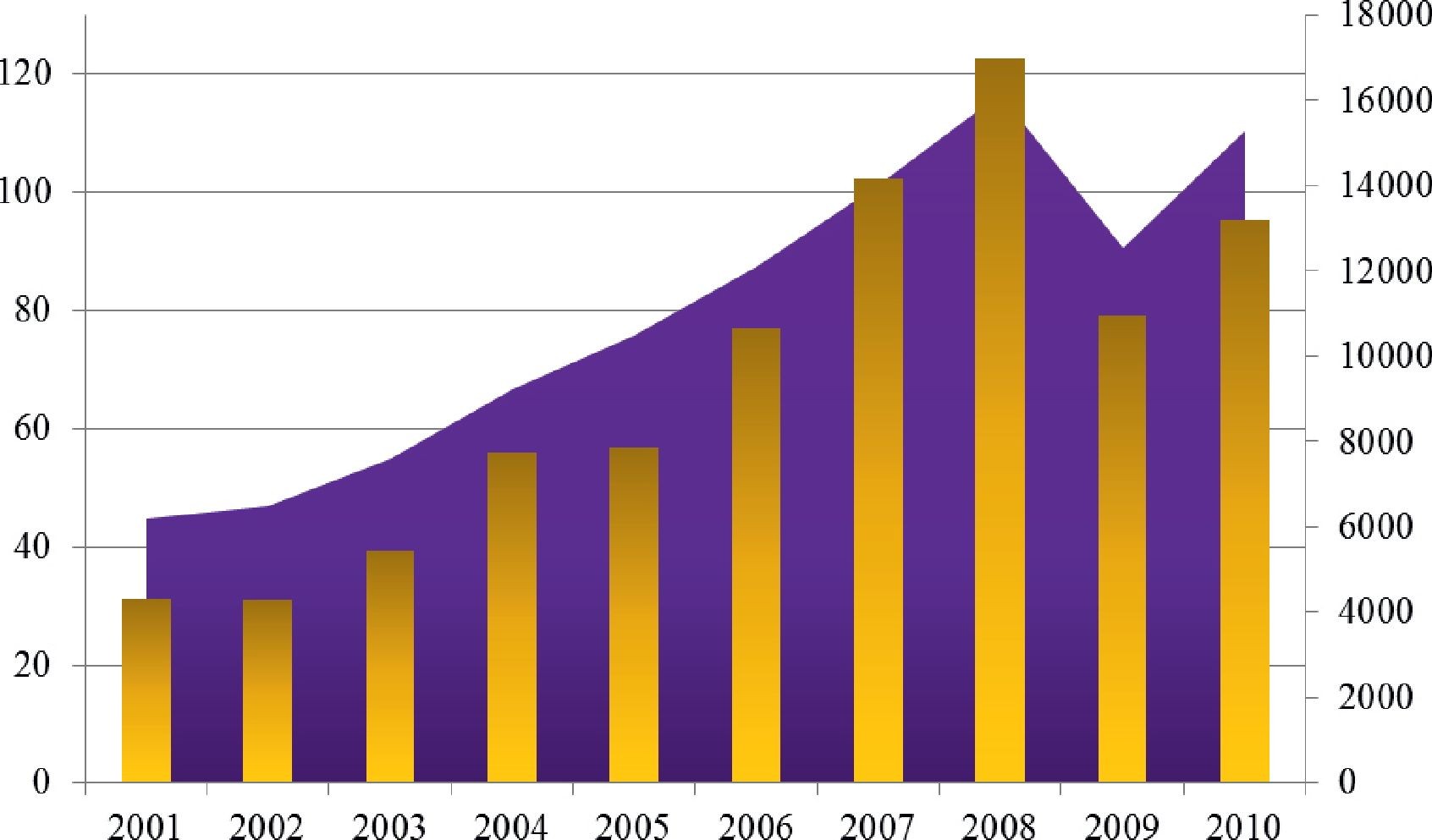

Apart from the GDP growth, foreign trade is one of the most important indicators for assessment of macroeconomic trends. The success of integration associations is often estimated in accordance with their performance in trade because intensification of trade volume is considered to be one of the main goals of integration in the first place. Therefore, free trade zones are often established in order to boost mutual trade. In this regard, it is important to consider the trade indicators in the EurAsEC countries in the period of 2001-2010. Similarly to the GDP analysis above, these figures are, then, com

pared with the world average trade indicators. Figure 3 shows the dynamics of the mutual trade of the Eurasian Economic Community in comparison with the world exports. As it can be seen, the growth in trade within the EurAsEC was more intense compared to the world trade increasing by 3.1 times (from $31.1 to $95.2 billion) while the world exports rose only by 2.5 times (from $6,194 to $15,283 trillion).

Figure 3. Foreign Trade of EurAsEC in 2001-2010 in Comparison with World Average

Sources: http://www.evrazes.com and http://unctad

Thus, there is an apparent pattern that the growth in trade within EurAsEC exceeded the world average. However, for having a more detailed picture, the foreign trade of the EurAsEC countries with their partners in the Community and that with the rest of the world should also be considered. Table 1 shows the data on the trade of the five EurAsEC member states from 2001 to 2010.

The table above shows that all the EurAsEC countries demonstrated a rapid increase in the foreign trade throughout the whole period from 2001 to 2010 of hundreds of percent. When the trade of the individual countries with their EurAsEC patterns is compared with the foreign trade figures with the rest of the world, the situ

|

Total |

Export |

Foreign Trade Turnover |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Including EurAsEC Countries |

Total |

Including EurAsEC Countries |

|||

|

Belarus |

2001 |

7451 |

4017 |

15737 |

9489 |

|

2008 |

32570,8 |

10992,4 |

71952,1 |

34687,8 |

|

|

2010 |

25225,9 |

10407,2 |

60094,1 |

28882,8 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

2001 |

8639 |

2063 |

15085 |

5118 |

|

2008 |

71183,5 |

7104,6 |

109072,5 |

21446,2 |

|

|

2010 |

59216,6 |

5704,6 |

88976,6 |

17350,1 |

|

|

Kyrgyzstan |

2001 |

476 |

161 |

943 |

402 |

|

2008 |

1855,6 |

526,6 |

5928 |

2441,4 |

|

|

2010 |

1759,8 |

731,7 |

4982,9 |

2257,3 |

|

|

Russia |

2001 |

100060 |

8778 |

141944 |

15534 |

|

2008 |

467580,6 |

38907,9 |

734681,3 |

56543,2 |

|

|

2010 |

396441,7 |

30519,6 |

625395,1 |

45412,9 |

|

|

Tajikistan |

2001 |

652 |

198 |

1340 |

576 |

|

2008 |

1408,7 |

146,4 |

4681,3 |

1585,5 |

|

|

2010 |

1195,2 |

135,7 |

3853 |

1346,6 |

|

|

EurAsEC Total |

2001 |

117278 |

15217 |

175049 |

31119 |

|

2008 |

583428 |

61074,3 |

941444,9 |

122660,9 |

|

|

2010 |

483839,2 |

47498,8 |

783301,7 |

95249,7 |

|

Table 1. Foreign Trade and Export of EurAsEC Countries in 2001-2010 in mln in $

Source: http://www.evrazes.com

ation is as following: the trade of Belarus with the rest of the world grew by 3.8 times, while its trade with its EurAsEC partners increased by 3 times. For Kazakhstan, those figures were

5.9 and 3.4 respectively; for Kyrgyzstan those were 5.3 and 5.6; Russia showed 4.4 and 2.9* Including Uzbekistan.

fold increase and Tajikistan’s growth in terms of its trade with the rest of the world grew by 2.9 times and the trade with its EurAsEC counterparts rose by 2.3 times. Thus, almost all the EurAsEC countries traded more elsewhere than within the Community.

As for the export, the comparison of the growth within the EurAsEC with the overall growth during the period from 2001 to 2010 shows the following results: in Belarus, it increased by 3.4 and 2.6 times respectively; in Kazakhstan, the figures were 6.9 and 2.8; in

Kyrgyzstan, there were 3.7 and 4.5-fold increases; Russia’s growth of its foreign trade with the rest of the world was 4-fold and with the other EurAsEC countries, it was 3.5-fold. The patterns in Tajikistan is different: it increased by 1.8 times its exports to the rest of the world but reduced it by 31% to the EurAsEC.

The data above shows that the EurAsEC countries expect Kyrgyzstan, traded with the world more than with each other and the foreign trade of Tajikistan with the EurAsEC even showed the negative growth.

The structure of the foreign trade of the EurAsEC countries appears to be a possible explanation of this. The raw materials constituted (and still do) the bulk of their export and there was more demand for them beyond the EurAsEC. As for the trade within the EurAsEC, those were predominately manufactures.

In the period from 2001 to 2010, there was a very rapid increase in the world prices for the commodities caused by strong liquidity in the markets. The commodities were gradually transforming from being the major resources for manufacturing into the investment and speculative instruments. Accordingly, the prices of the raw material exports grew much more rapidly than the prices of the other goods, thus, the rapid growth of the exports from the EurAsEC to the countries beyond since 2011, after the turbulence of the world markets had stopped and the prices stabilized. This effected the pattern of the foreign trade of the EurAsEC. These trends are even more apparent when one analyses the indicators the EurAsEC countries showed after being integrated into the EEU.

Apart from the macroeconomic indicators, the popular wellbeing is also important to understand the impact of the Eurasian integration on the countries concerned. This may be translated into such indicators as income per capita or nominal wage. These indicators are not less illustrates for the purposes of the assessment of the effectiveness of a economic policy (in this case the integration initiatives) than traditional GDP.

During the period of formation and consolidation of the Eurasian Economic Community these indicators grew very intensively surpassing the growth rates of the main macroeconomic indicators discussed above (Table 2).

Table 2. Average Monthly Nominal Wages in EurAsEC Countries in 2001 - 2010 in $**

|

2001 |

2010 |

Growth Rate (Times ) |

|

|

Belarus |

87 |

414 |

4,8 |

|

Kazakhstan |

118 |

526 |

4,5 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

30 |

155 |

5,2 |

|

Russia |

111 |

686 |

6,2 |

|

Tajikistan |

10 |

81 |

8,1 |

Source: http://www.evrazes.com

The table above shows how the average monthly wage increased in the EurAsEC countries in the period from 4.5 to 8.1 times. This kind of increase may also be considered as a sign of the positive impact of the Eurasian integration and this time it reached common people.

The Eurasian integration entered its new stage in 2011 when the Eurasian Customs Union was established. This time the integration meant a single customs tariff regime and territory as well as a supranational body, which initially has been functioning as the ECU Commission and then was transformed into the Eurasian Economic Commission granted considerable powers in the following areas:

** The Indicators are taking into account the official annual average exchange rate to the USD throughout the period.

- import customs duties;

- trade regimes in relation to the third countries;

- statistics of foreign and mutual trade;

- macroeconomic policies;

- competition policies;

- industrial and agricultural subsidies;

- energy policy;

- natural monopolies;

- government and(or) municipal procurement;

- mutual trade in services and investment;

- transport and communication;

- monetary policy;

- intellectual property and patenting;

- labor migration;

- financial markets (banking, insurance, cur rency and securities markets);

- tariff and non-tariff regulation;

- customs administration.

The ECU, as a new phase of the Eurasian integration of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia, is analyzed further in terms of its economic developments in order to understand how the integration of a higher level changed the extent and results of the cooperation.

While analyzing the economic performance of the countries members of the ECU via using the traditional instruments, there are two important moments to remember. Firstly, this kind of analysis is only possible with the data collected since 2011 when the EUC actually started to exist but not since 2007 when it was technically established. Secondly, the three years is a rather short period to enable a robust analysis to in- dentify and understand long-term trends. At the same time, the positive changes in the longest run possible was(is) the major goal the ECU was created for after all. Yet again, the three- year data is not enough to make a final conclu

sion about the character of the changes on the macroeconomic indicators. However, during these three years, the bulk of the indicators increased.

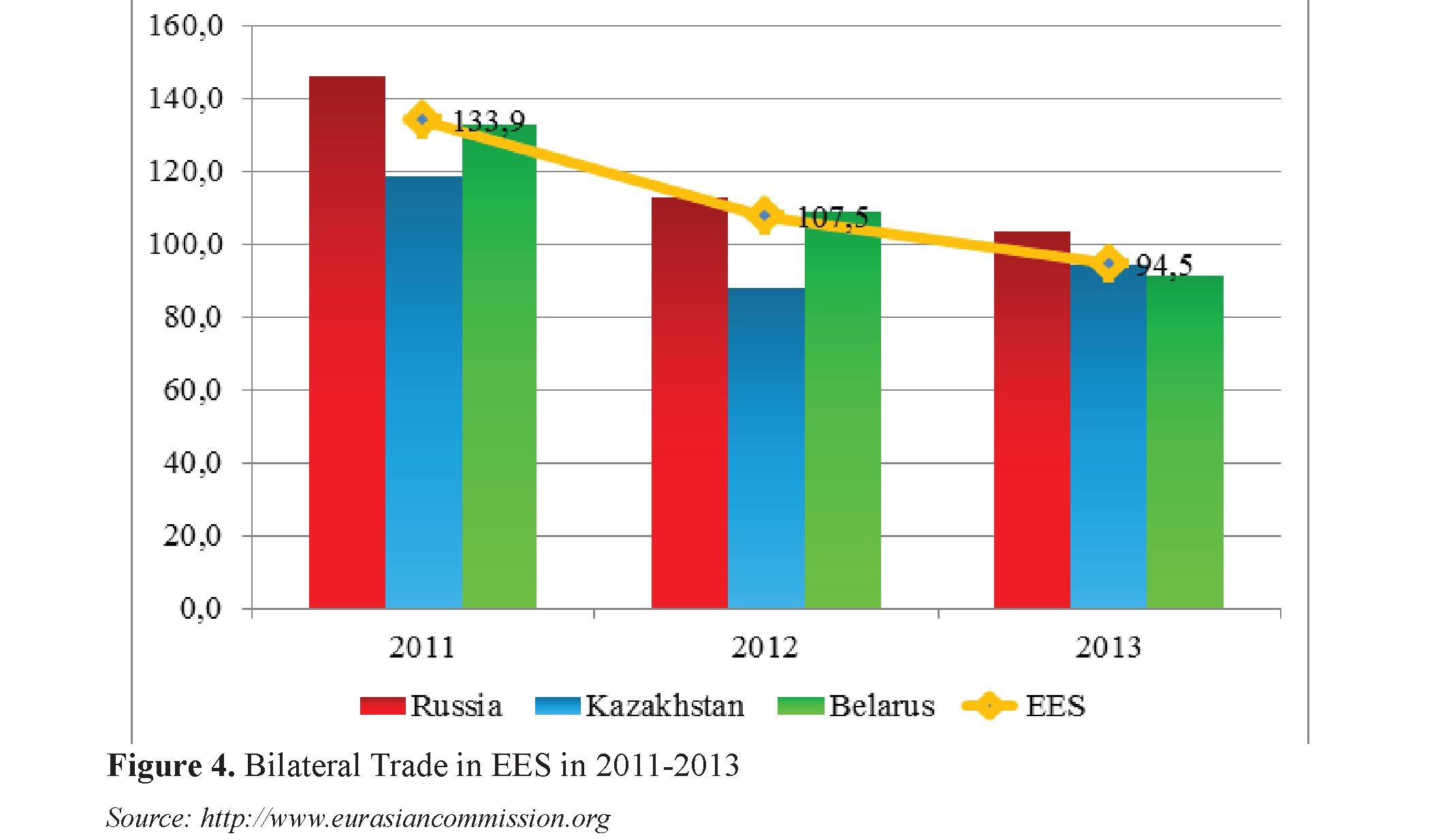

The volume of the mutual trade among the ECU countries increased during the two first

years, then the growth slowed and in 2013, the indicator dropped slightly (Figure 4).

years, then the growth slowed and in 2013, the indicator dropped slightly (Figure 4).

Russia demonstrated the reduction in its exports in 2013 of 91.2% compared to 2012, there was also negative growth of 94.1% in the same period in Kazakhstan, while Belarus managed to increase its exports by 3.4 %. It should be noted that there was a considerable decline in the growth rate of the mutual trade of the ECU as a whole since it entered into actual existence in 2011. In 2011, the growth amounted to almost 134% with respect to the previous year whereas in 2013 the figure was only 94.5%.

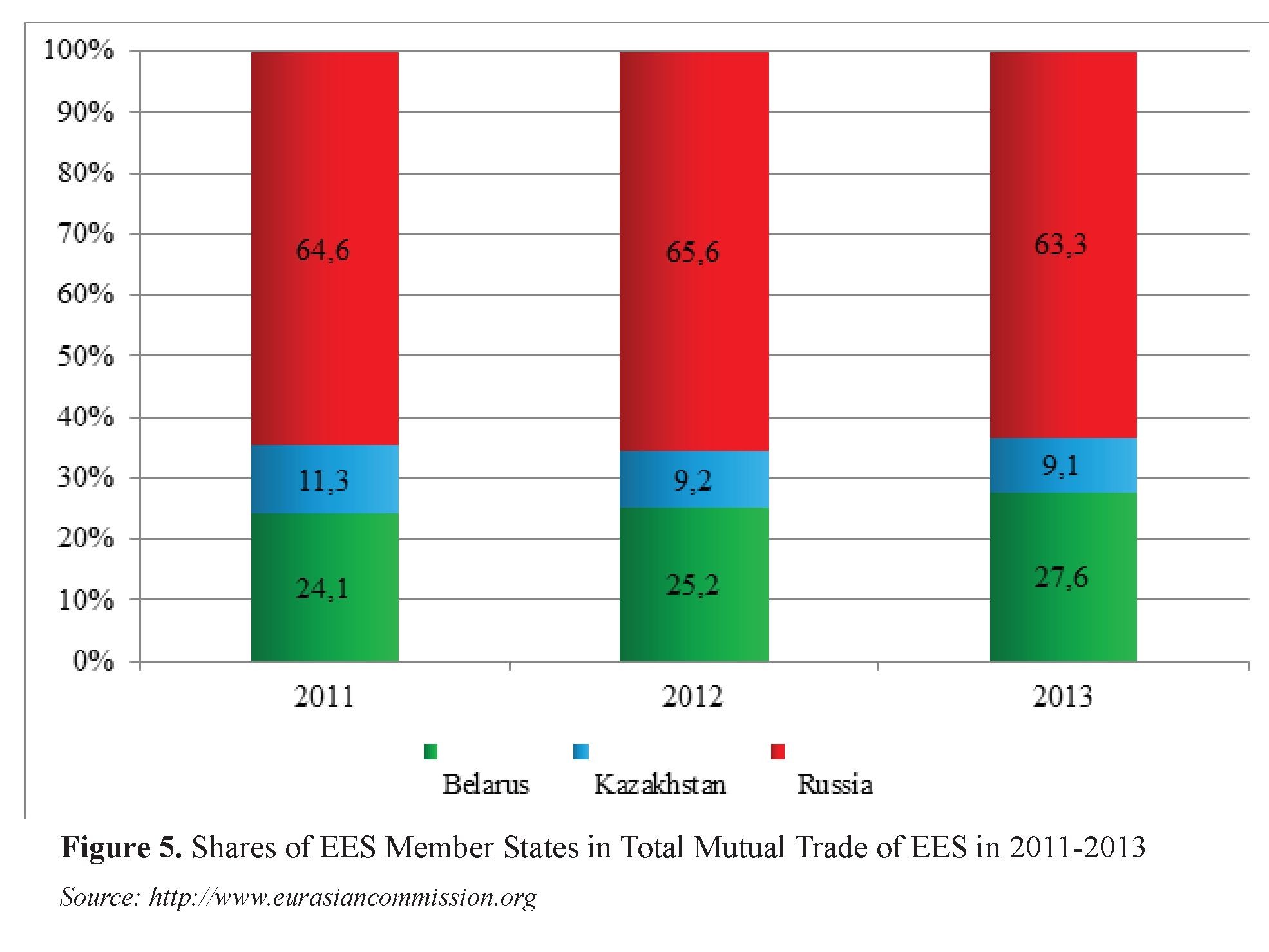

Belarus was the only country that consistently increased its exports to its EES fellow member states. Therefore, Belarus enlarged its share in the total EES turnover to 27.6 %, while Russia and Kazakhstan demonstrated the negative growth. The share of Kazakhstan, for instance, decreased steadily during the two years reaching 2.2%. The volume of its trade with its EES partners was not adequate to the economic potential of the country such (Figure 5).

Although stating the decrease in the volume of trade in 2013 was significant, a more important observation would be that it was the first time during the three years of the ECU/EES existence when the mutual trade within grew at a slower pace compared to the total exports of the individual member states (Table 3). If in 2011 and 2012 the volume of the mutual trade within the ECU/EES exceeded quite noticeably the total exports of the member states beyond the ECU/EES, in 2013, however, the figures were 94.5%.and 98.6% respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Mutual Trade within ECU and Beyond, Index***

Source: http://www.eurasiancommission.org

|

Trade with Third Contries |

Mutual Trade with ECU Counters |

|||

|

Volume |

Export |

Import |

Export |

|

|

2011 |

132,2 |

133 |

130,8 |

133,9 |

|

2012 |

103,0 |

102,1 |

104,6 |

107,5 |

|

2013 |

99,6 |

98,6 |

101,4 |

94,5 |

Despite the slowdown of the foreign trade in 2013, the grand total during the all three years of the Customs Union’s existence is still positive as the mutual trade within the ECU grew faster than the trade beyond the Union both in 2011 and in 2012. There are two possible explanations of the slowdown in the mutual trade in 2013.

According to the Eurasian Economic Commission, the main reason for the decline in mutual trade was the sharp reduction in the supply of oil from Russia to Belarus: (in 2012 compared with 2011 their volumes dropped by 1 5 times). When excluding the fuels from the analysis, the data shows that the mutual trade within the ECU/EES, compared with January- December 2012 increased by 0.3 [6].

Another major reason why the dynamics of the mutual trade within the ECUEES declined in 2013 was the decrease of the commodity prices. More importantly, these were the prices of the particular commodities, primarily the metal ores that are the bulk of in the mutual trade among the ECU member states.

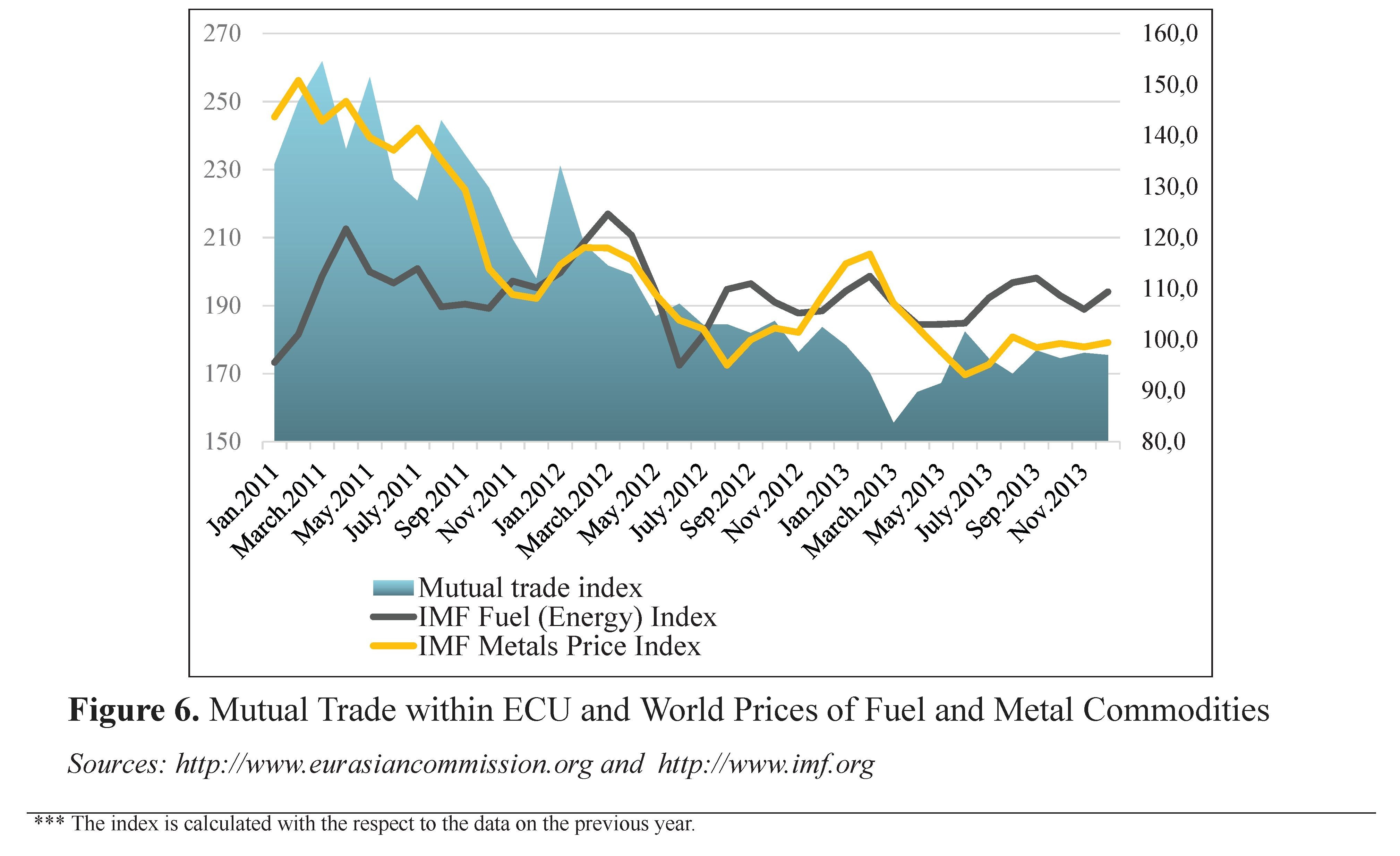

The second explanation appears even more plausible when one compares the growth in the ECU mutual trade of the metal ores and mineral commodities and the prices for these particular kind of commodities (Figure 6). The figure

shows the comparative dynamics of the commodity prices for fuel and metals calculated by the IMF in their relation to the growth of the mutual trade within the ECU/EES; the price index of the industrial metals decreased continuously from January 2011 to November 2013.

shows the comparative dynamics of the commodity prices for fuel and metals calculated by the IMF in their relation to the growth of the mutual trade within the ECU/EES; the price index of the industrial metals decreased continuously from January 2011 to November 2013.

T150 correlation of the volume of the mutual trade among the ECU member states and the prices of metal commodities, which were constantly decreasing, was the most apparent trend throughout the whole period of the ECU actual functioning from 2011 IM uFtu Fauetrla (Eenenrgeyx) Inde

The proportion of IMF Metals Pricey Index trade of the ECU countries was relatively high when compared with the exports to other countries of the world. This appears to be the major reason why the former exceeded the latter: the metal ores are virtually absent in t 80 0xports of the EES countries outside the CIS. I , the structure of the exports beyond the CIS the “mineral products” rubric is almost exclusively fuel. Thus, in 2013, the share of fuel in the mineral product export beyond the CIS amounted to 98.6 % [7].

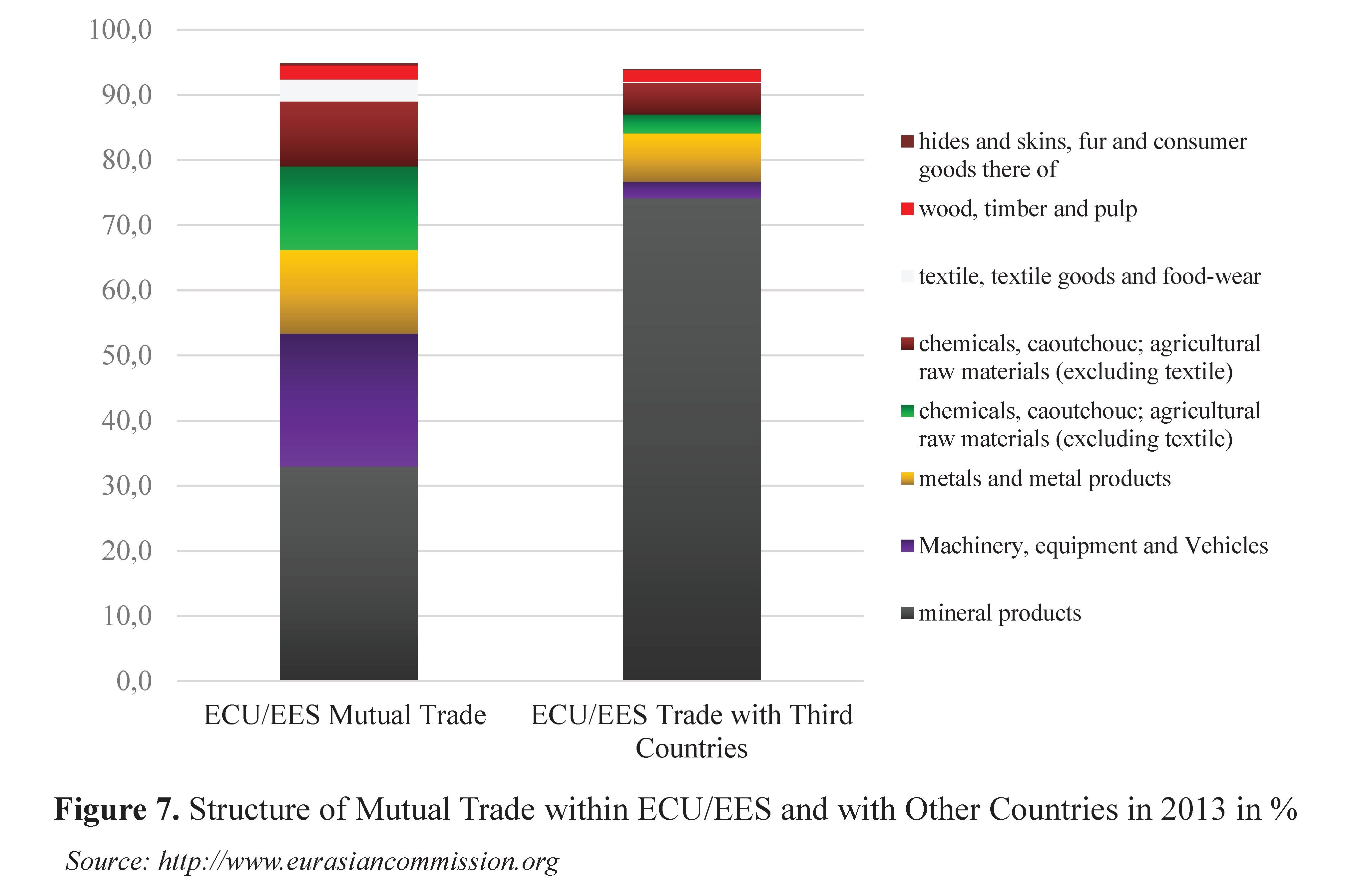

It is also important to note a considerable difference among the individual member states in terms of the structure of their mutual trade within the EES and their export beyond (Figure 7).

As it can be seen on figure above, the export of the EES as a whole is mostly the raw materials, i.e. mineral and metal commodities (81.5%); the share of these commodity groups in the mutual trade was only 45.9 %. Thus, the indicators of the export from the EES to the third countries were effected much more by the considerable fluctuations of the world com modities prices (substantial growth in volatility in the global markets of oil and metals in the recent years) than those of the mutual trade where the share of these commodity groups was smaller.

Given the trends above, it would be reasonable to foresee that the volume of the export from the EES to the third countries will be larger than the volume of the mutual trade provided the prices of oil and metals continue to grow. The reverse process is more likely if the growth of oil and metal prices on the world markets slows down; in this case, the volume of the mutual trade within the EES may exceed the export beyond.

These were the major reasons why the growth rates changed so much during the three years of the ECU/EES genuine functioning as well as the trade indicators of the EurAsEC - described above in this paper - when the trade with the countries beyond the Community in- creas faster than the mutual trade within the EurAsEC itself. These were the times when the world oil prices grew very rapidly making the member states intensify their export to the outside world. As soon as the prices stabilized and even rolled back, the mutual trade increased while the impact of the oil factor decreased.

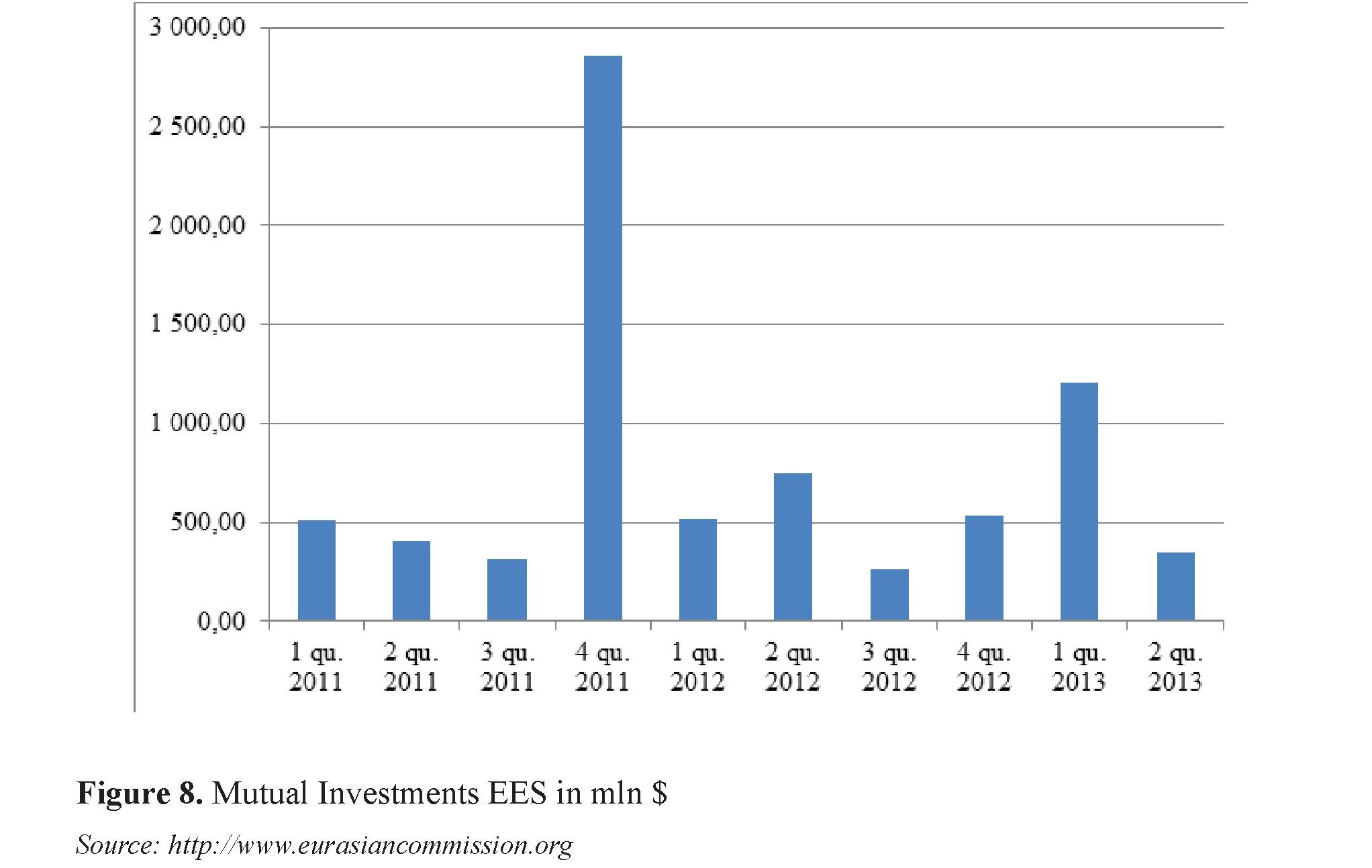

Apart from the mutual trade, the investment cooperation may also be considered as an useful indicator of the dynamics within the integration. The analysis of the figures on the mutual investment in the period of 2012-2013 does not enable to make any concrete conclusions, however, some figures may be rather illustrative. Thus, the volume of the mutual direct investment reduced significantly in 2012 comparing with 2011 and increased slightly again in the first half of 2013 if compared to the same period in 2012 (Figure 8).

The data on the mutual investment within the ECU/EES is not suffice to reveal any trends due to a number of reasons. For example, the statistics cannot be considered adequate if we remember the investment flows that were tech nically coming from beyond the EES, but actually originated within the EES countries. The insufficient length of the period when the data was collected also prevents from indentifying accurately the trends and patterns of the mutual investments within the ECU/EES. Moreover, the volume of the investments within the ECU/ EES was not that large. This is why the indicators demonstrated rather high volatility. For instance, the sharp increase of the volume of the mutual investments in the fourth quarter of 2011 (Figure 7) was caused by singular transaction when the Russian Gazprom purchased of 50% stake in the Belarusian Beltransgaz for $2.5 billion making its stake in the company

100% [8]. Therefore, in order to have a more clear picture about the trends in the mutual investment within the ECU/EES, one may rely on the analysis of the indicators of a more relativistic nature.

The share of the individual ECU member states in the total volume of the foreign investment in the economy of each of the ECU coun-

try may be considered as one of the indicators enabling to understand the impact of the economic integration. It is obvious, however, that the investments from Kazakhstan or Belarus are not significant for the economy of Russia, while the investments from the other EES states, primarily from Russia, to both Belarus and Kazakhstan are very important (Table. 4).

Table 4. Direct Investment from EES Countries in Total FDI in EES in %

|

2011 |

2012 |

1st Half-year 2013 |

|

|

Belarus |

70,5 |

30,7 |

37,3 |

|

Kazakhstan |

7,9 |

8,7 |

13,7 |

|

Russia |

0,3 |

0,8 |

0,3 |

Source: http://www.eurasiancommission.org

The table above shows that Russian investments were especially significant for the econo

my of Belarus (there was any FDI from Kazakhstan to Belarus). The situation did not change much even after the Gazprom deal in 2011; the share of the Russian investments remained very high throughput 2012 and 2013. Since the ECU had been established, Kazakhstan demonstrated a steady growth of the indicator that may be considered as an indirect evidence that our participation in the cooperation in the field of investment within the broader process of Eurasian economic integration was, generally, a success.

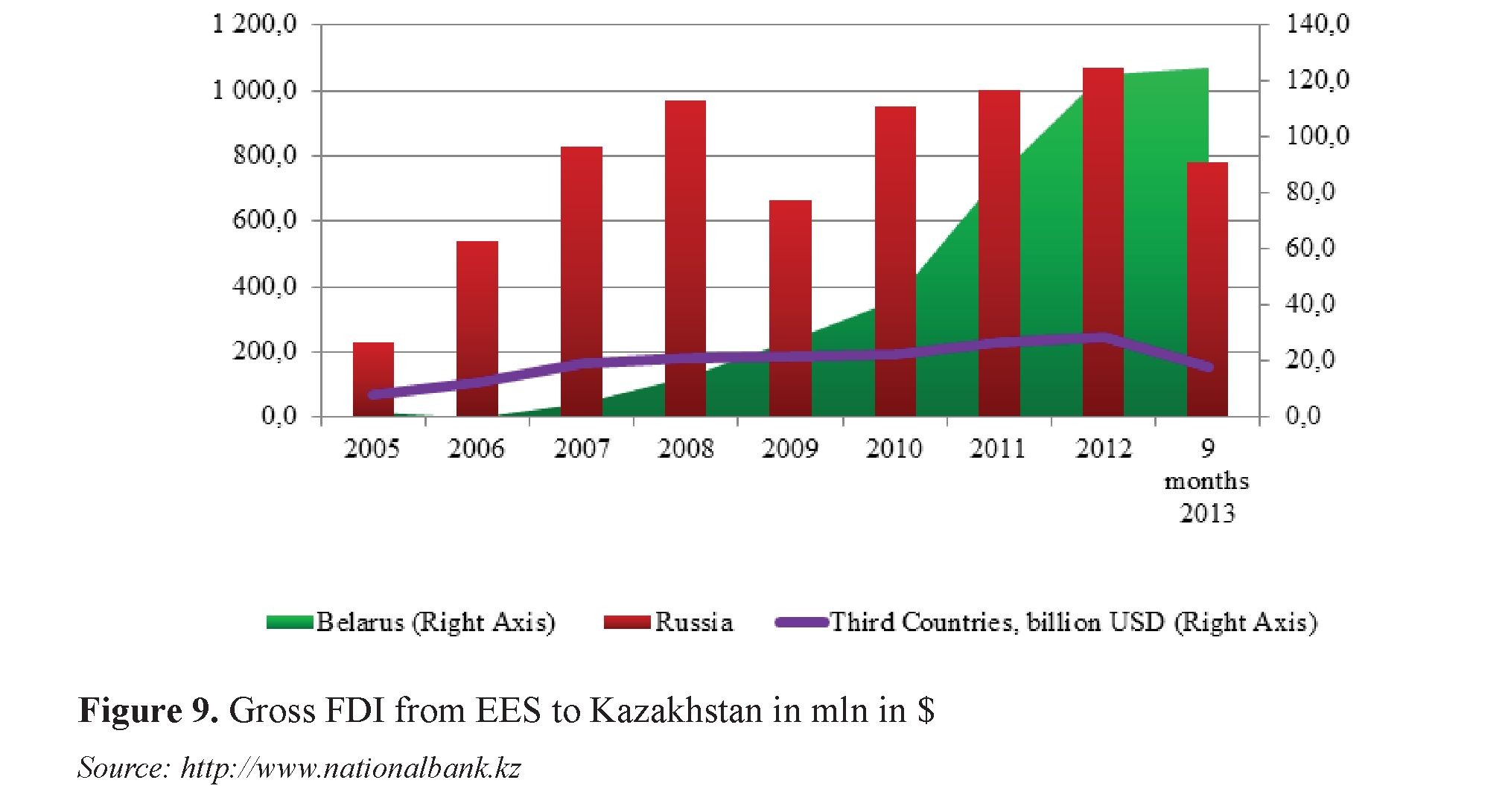

Kazakhstan’s case is useful to understand the role of various factors in the dynamics of the cooperation in the field of investment within

the ECU/EES. First of all, it should be noted that there was no any considerable decreases not only in terms of the EES investment share (Table 4), but in the absolute size of the of investments coming from the ECU/ESS member states (Figure 9).

the ECU/EES. First of all, it should be noted that there was no any considerable decreases not only in terms of the EES investment share (Table 4), but in the absolute size of the of investments coming from the ECU/ESS member states (Figure 9).

Since 2010, there was steady annual growth of FDI from Russia and Belarus to Kazakhstan; moreover, the growth exceeded that of the FDI from the third countries. From 2009 to 2012, the total volume of the FDI in Kazakhstan rose by 34,6% whereas the investments from Russia grew by 61,1 % and those from Belarus increased in 4,5 times.

Therefore, as the data shows, there was no any decay in terms of the investment cooperation of the ECU/EES countries throughout the entire period. However, it is important to remember that the rate of the investment growth may slow in the future due to the impact of the external factors; the example of how the world economic crisis of 2007-2009 reduced the FDI from Russia to Kazakhstan in 2009 is rather illustrative.

It also sensible to expect that the investment regime may change qualitatively as long as the overall cooperation within the integration enhance due to the establishment of the single financial market enabling the participants to make transactions with their the ECU/EES counterparts.

It is also noteworthy that Kazakhstan’s financial involvement in Russia and Belarus was predominantly not in the FDI format but falling into the rubric of the “other investments” and “portfolio investments”. In particular, the volume of accumulated other investments (mainly borrowing) from Kazakhstan to Russia at the end of the 3rd quarter of 2013 was $7.585 billion while the FDI was only $672 million. The volume of portfolio investments from Kazakhstan to Russia was even less amounting only $310 million. As for the investments from Russia to Kazakhstan, the situation was similar with the figures of $4006 and $38 million respectively exceeding the volume of accumulated direct investments that were $2.034 billion [9].

To sum up, the data shows that the investment cooperation in the spheres other than the FDI appears to be more potent, it is more likely to grow further as long as the integration itself enhances in future.

Prospects of Eurasian Integration under the Eurasian Economic Union

The treaty on Eurasian Economic Union was signed in 2014. The Eurasian Economic Union started functioning on January 1st, 2015. The Treaty is comprised of the two parts dealing with institutional and functional matters respectively where the format of the Union is stipulated in terms of its structure, bodies, managerial matters, procedures of accession of new members etc. The Treaty sets the goals in the following spheres of the integration within the Union: trade, technical regulation, industry and agriculture, natural monopolies, transport and energy, competition and public procurement, taxes, monetary policy and financial markets, intellectual property, services and investment, labor migration, macroeconomics and statistics.

The overall end the current stage of the integration is aimed at is rather obvious. It is to build and enhance the supranational bodies to manage and expand the common economic regime reaching all key spaces; having started with building of the single market for goods and services (the ultimate goals of the Customs Union) and proceeding to the genuinely functioning single market for goods, services, capital and labor.

It has been clear so far that the EEU has been limited to the economic matters. Currently, at the first stages of its establishment, not only po

litical but also social, humanitarian and cultural affairs remain within the powers of the governments of the member states or are to be dealt with within the other formats [10].

Being an organization of a higher level of integration, the EEU will not only push the existing international institutions to enhance their role in carrying out a coordinated economic policy, but will also build new ones. Technically, the Union shall embrace the institutions that have been functioning within the EurAsEC, namely the Eurasian Development Bank, Crisis Fund and Center for High Technology as well as other organizations and institutions of a more political nature such as the Parliamentary Assembly, the EurAsEC Court, number of agencies and commissions.

The establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union puts the end to the Eurasian Economic Community. Back in May 2013, First Deputy Prime Minister of Russia Igor Shuvalov stated that the EurAsEC would cease to exist and all the institutions of the Eurasian Economic Community would be transferred into the Eurasian Economic Union on January 1st, 2015 [11].

The second most significant initiative - artic ulated by First Deputy Prime Minister of Russia Igor Shuvalov back in March 2014 - is to create a single supranational financial banking regulator by 2025 that will be located in Kazakhstan.

The Union, being a system of the old and new institutions combined with the realization of the four economic freedoms within a single market, namely free movement of goods, services, capital and labor, is drawing the contours for the further integration. After being finally consolidated, the Union is supposed to

be transformed into a genuine single economic space without any barriers for the basic factors of production founded on the consensus among the member states on the matters of economic policy in the key spheres, namely macroeconomic, monetary, tax and labor policies. It also would mean having consolidated institutionalized mechanisms aimed at stimulating further development and preventing possible negative impact of external crises.

According to President Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan, the Eurasian Economic Union is a project that is adequate to the immensity of the current and future challenges. The EEU has all it takes to become an integral part of a new global architecture that has been forming after the financial and economic crisis [3].

President Putin of Russia, having stressed the significance of the EEU for establishing the regime that would enable conduction of a coordinated economic policy, said that the Union should be granted considerable powers of economic regulation as this would boost coordination in the key spheres, increase stability and enhance potential of the economies of the member states making its single market more capacious and attracting more investments [12].

President Lukashenko of Belarus also stressed that the economic role of the Union should prevail over the domestic decisionmaking. He drew the attention to the necessity to have a very defined hierarchy in terms of the le

gal force of the acts of the Union bodies. President of Belarus insisted that the resolutions of both the Supreme Council and the Intergovernmental Council would be binding on all parties [13].

The membership in the Eurasian Economic Union, provided all intended moves and policies are implemented successfully, is more beneficial in terms of economic prospects for the

EEU countries than an independent path. The free movement of the basic factors of production shall stimulate all business activities, enhance competition in the domestic markets of the member states that shall, in turn, encourage the production sector to increase its effectiveness and all other participants in the economy to be more efficient because choice shall increase

as well. The single market shall mean more direct foreign investments, particularly from those strategic foreign investors from abroad who shall be attracted by the common market of the EEU. This is very significant for smaller

economies, namely those of Belarus and Kazakhstan.

The other advantage of the Eurasian Economic Union is that it will facilitate harmonization of the economic policies of the member states that shall improve overall economic management and enable to focus the resources both directly (via the resolutions of the EEU bodies and through the certain institutions aimed specifically at development) to realize the projects

of much larger scale that, otherwise, would be impossible. The common institutions for anti-crisis management shall also enhance the Union’s capacity to deter and mitigate possible negative consequences of the external factors similar to those resulted from the recent world economic crisis.

The features above will, in our belief, enable the EEU to boost socio-economic development of the member states in the long run due to a number of reasons. The enhanced business within the single economic space shall accelerate trade, attract investment and increase aggregate demand. It also shall enhance capacities of the economies of the participating countries to resist negative external impacts. Importantly, the possible effect on the economies of the individual countries from their participation in the EEU will be proportional to the size of their economy as such; in other words, the lower the GDP, the greater shall the positive influence of the integration be on the economy and vice versa.

Тhe other reason why membership in the EEU may affect the individual states differently is the features of their economies. For example it may boost the export to the other EEU countries or increase the volume of the investment. As for the total GDP growth of the entire EEU, the analysis of the other cases of integration of the similar kind (customs union and free trade zones elsewhere in the world) suggests that the additional GDP growth may be expected as much as 0,3-0,6% per year throughout the entire period of the Union’s existence.

SOURCES:

- Alma-Ata. Protocol. http://www.cis.minsk.

- Назарбаев Н.А. Выступление в МГУ им. Ломоносова 29 марта 1994 г. Н.А.Назарбаев. Том II. Избранные речи 1991-1995 гг. – Астана. ИД «Сарыарка», 2009., сс. 439-440.

- Назарбаев Н.A. Евразийский Союз: От идеи к истории будущего. «Известия-Казахстан», 26 октября 2011 г.

- Евразийское Экономическое Сообщество. История. Официальный сайт ЕврАзЭС. http://www.evrazes.com.

- Евразийская экономическая интеграция: цифры и факты. Евразийская экономическая комиссия, 2014. сс. 6-7. ttp://www.eurasiancommission.org.

- Об итогах внешней и взаимной торговли товарами Таможенного союза и Единого экономического пространства за январь-декабрь 2013 г. Евразийская экономическая комиссия, 2014. http://www.eurasiancommis- sion.org.

- Экспорт и импорт товаров ТС и ЕЭП по укрупненным товарным группам в торговле со странами вне СНГ. Товарная структура внешней торговли государств - членов ТС и ЕЭП. Евразийская экономическая комиссия. http://www.eurasiancommission.org.

- Долева, А.А. Прямые иностранные инвестиции в Беларусь. NovaBelarus. com. СЕНТЯБРЬ - 7 – 2012. http://ru.novabelarus.com.

- Международная инвестиционная позиция (МИП) Казахстана по странам. Международная инвестиционная позиция. Национальный банк Республики Казахстан, 2014. http://www.nationalbank.kz.

- Сагинтаев Б.А. Предмет договора ЕЭС - исключительно экономическое сотрудничество - первый вице-премьер РК. 08 Апреля 2014. http://www. kazpravda.kz.

- Шувалов И.И. Все институты ЕврАзЭС будут погружены в Евразийский экономический союз с 2015 года -- первый вице-премьер России. Агентство Синьхуа, 2013-05-30. http://russian.cri.cn.

- Путин B.В. Евразийский экономический союз заработает с 2015 года. Российская газета, 05.03.2014. http://www.rg.ru.

- Лукашенко А.Г. Евразийский экономический союз должен быть международной организацией. БелТА, 24 декабря 2013. http://www.belta. by/ru.