INTRODUCTION

Recently, the integration of English language learning together with subject-matter content at all levels of educational system has attracted great interest of EFL teachers, researchers, and curriculum designers in Europe as well as in other parts of the world. This integration includes several approaches and Content and Language Integrated Learning is considered as one of them. At the current stage, CLIL has considerable impact on languages education reform and policy due to its effectiveness in promoting high quality gains in language proficiency, student engagement, and retention. International research has also established numerous other benefits of the CLIL approach to EFL teaching, such as increasing degree of students’ motivation and heightening level of intercultural awareness and competence.

To understand the whole concept of CLIL we should have a look at its origins, components and distinctive peculiarities, as well as at its already existing research outcomes. In the following sections, our main objective will be to cover the main ideas concerning CLIL and to view specific demands in terms of effective teaching and learning in the light of theoretical framework and thorough analysis of the literature concerning the issue.

ORIGINS AND STRUCTURE OF CLIL

The precise definition of Content and Language Integrated Learning appeared first in 1994. The European researchers Mehisto, Marsh and Frigols presented a new term claiming that “CLIL is a dual-focused educational approach in which a foreign language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language” (2008, p. 9). The whole approach was originally based on the welldocumented success of the Canadian immersion model for language teaching, in which mainstream curriculum content is delivered through the students’ non-native language. Besides, content-based language teaching was a common approach to language teaching in the United States around the 80s which was aimed to offer alternatives to the classroom practices used with learners from immigrant communities.

Since 1990s, the term CLIL evolved as an umbrella term encompassing various forms of learning in which a language performs a special role alongside the learning of any certain subject or content. This term has been adopted by various European researchers and universities as a generic term for such programs and integrated curricula. The current processes of globalization have made CLIL an opportune solution for governments concerned with developing the linguistic proficiency of their citizens as a defining key for economic success. There was already some dissatisfaction with traditional EFL teaching approaches and a conception that they were not bearing fruit. CLIL offers a budgetary efficient way of promoting multilingualism without overwhelming existing curricula. With its emphasis on the convergence of curriculum areas and transferable skills, CLIL also appears to serve well the demands for increased innovation capacity and creativity.

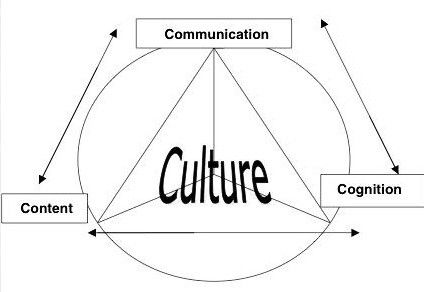

The main structure of CLIL contains four significant elements which refer to four key “building blocks” (Coyle, 2006, p. 9), known also as the 4Cs Framework:

- Content: the subject matter, theme, and topic forming the basis for the program, defined by domain or discipline according to knowledge, concepts, and skills (e.g. Science, IT, Arts).

- Communication: the language to create and communicate meaning about the knowledge, concepts, and skills being learned (e.g. stating facts about the universe, giving instructions on using personal computer, describing emotions in response to fiction and art).

- Cognition: the ways that we think and make sense of knowledge, experience, and the world around us (e.g. remembering, understanding, evaluating, critiquing, reflecting, creating).

- Culture: the ways that we interact and engage with knowledge, experience, and the world around us; socially (e.g. social conventions for expressing oneself in the target language), pedagogically (e.g. classroom conventions for learning and classroom interaction), and according to discipline (e.g. scientific conventions for preparing reports to disseminate knowledge).

Figure 1. The CLIL 4Cs Framework (Coyle, 2006, p. 551).

As Coyle goes on to elaborate: “The 4Cs Framework suggests that it is through progression in knowledge, skills and understanding of the content, engagement in associated cognitive processing, interaction in the communicative context, developing appropriate language knowledge and skills as well as acquiring a deepening intercultural awareness through the positioning of self and “otherness”, that effective CLIL takes place. From this perspective, CLIL involves learning to use language appropriately whilst using language to learn effectively” (p. 9).

Sometimes in the research papers of other authors the central focus is shifted to another component, for example, to content or communication instead of culture, as Coyle claims. However, the interrelationship between subject-matter knowledge and language knowledge through all these four components, which are holistically considered in various models, leads to the developed multilingual competence. Furthermore, CLIL is based on six contextually sensitive and flexible pedagogical principles for integrating language and content that work across different contexts and settings, while incorporating all four key elements of underlying 4Cs framework:

- Subject matter is about much more than acquiring knowledge and skills. It is about the learner constructing his or her own knowledge and developing skills which are relevant and appropriate.

- Acquiring subject knowledge, skills and understanding involves learning and thinking that is cognition. To enable the learner to construct an understanding of the subject matter, the linguistic demands of its content as the channel for learning must be analyzed and made accessible.

- Cognition requires analysis in terms of the linguistic demands to facilitate development.

- Language needs should be learned in context that is through the language, which requires reconstructing the subject themes and their related cognitive processes through a foreign or second language e.g. language intake or output (Krashen, 1985).

- Interaction in the learning context is fundamental to learning. “If teachers can provide more opportunities for exploratory talk and writing, students would have the chance to think through materials and make it their own”. (Mohan, 1986, p. 13) This has implications when the learning context operates through L2 (Pica, 2002).

- The interrelationship between cultures and languages is complex. The framework puts culture at the core and intercultural understanding pushes the boundaries towards alternative agendas such as transformative pedagogies, global citizenship, student voice and “identity investment” (Cummins, 1996).

The results are experiences in the educational sphere that promote greater possibilities for authentic and purposeful meaningmaking through language, by facilitating the development of new communicative skills while learning new content, understanding, and knowledge. Moreover, the dual focus of CLIL implies the relationship between language and content has to be totally transparent. In this sense, CLIL exposes the linguistic issues in subject content in a way that is often absent in non-language subjects. This makes CLIL teachers more aware of the linguistic needs of the learners and thus more effective at ensuring comprehension.

CLIL EFFECTIVENESS: BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES

Most studies on CLIL concentrate on the many structural difficulties surrounding its implementation. From a lack of persistent teacher supply and inadequate preor inservice training, to the limitation in sourcing teaching materials, the road to CLIL is not straightforward even for the most committed. This paper wants to observe some theoretical research outcomes and analyze critically some of the claims which rest on CLIL’s integral peculiarities. The special interest for us and, therefore, focus lies in the cross-curricular model of CLIL, on which the majority of research is carried out. By reviewing some of the latest evidence and considering the interaction between CLIL’s features and contextual factors, this review will try to provide a clearer picture of CLIL’s potential and its limitations. The main claims contained in the literary sources can be summarized here as following:

- CLIL leads to a higher level of attainment in EFL;

- CLIL improves motivation in all learners;

- CLIL benefits learners of all abilities;

- CLIL increases intercultural awareness.

In effect, CLIL provides the basic conditions under which students successfully acquire any new language: by understanding and then creating meaning (Lightbown & Spada, 2006). For first language acquisition, this occurs as infants are gradually exposed to new language in their first four to six years of life, matched against corresponding levels of early cognitive development. In contrast, traditional second language lessons typically focus and do it often exceptionally on the language elements – such as grammar, vocabulary, and other items or aspects (spelling, pronunciation, etc.) – while deliberately seeking to avoid exposure to what might be perceived as difficult or challenging content.

As a pedagogy, CLIL provides a comprehensive framework that recognizes the complex but necessary interrelationship between language and content for genuine language development. It does this together with a theoretically rich and solid set of principles to help guide teachers on how this can actually be achieved in practice, across a varied range of educational settings.

There is no any surprise that CLIL students have been found to be typically more engaged than students in regular programs, due to the authenticity of the content that drives the learning experience (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010; Mehisto, Marsh, & Frigols, 2008). Despite studying the same curriculum in their non-native language, CLIL students show to perform, on average, at least as well on tests of content knowledge than those learning the same curriculum material in their first language (Dalton-Puffer, 2008).

What is more interesting, CLIL students have also been shown to demonstrate higher levels of intercultural competence and sensitivity, including more positive attitudes towards other cultures. There is some reasons offered by Muñoz (2002, p. 36) for why CLIL tends to produce so many positive outcomes for learning. The key factors include:

- Learners benefit from higher quality teaching and from input that is meaningful and understandable.

- CLIL may strengthen learners’ ability to process input, which prepares them for higher-level thinking skills, and enhances cognitive development.

- In CLIL the learners’ affective filter may be lower than in other situations, for learning takes place in a relatively anxiety-free environment.

- Learners’ motivation to learn content through the foreign language may foster and sustain motivation towards learning the foreign language itself.

It also has to be mentioned that CLIL has two distinctive features that set it apart from other types of provision. The first one is the integration of language and content. In CLIL, the two elements are interwoven and receive equal importance, although the emphasis may vary from one to another on specific occasions. The aim is to develop proficiency in both by teaching the content not in, but with and through the foreign language.

The second distinctive feature is the flexibility of CLIL to accommodate the wide range of social and political as well as cultural realities of the environment context. CLIL models range from theme-based language modules to cross-Content and Language Integrated Learning curricular approaches where a content subject is taught through the foreign language. The latter model has become the most prevalent in the world in the last few years.

The rationale for CLIL rests on a number of points based on second language acquisition theories. With its integration of content and language, CLIL can offer an authenticity of purpose unlike that of any communicative classroom. CLIL provides learners with a richer, more naturalistic environment that reinforces language acquisition and learning, and thus leads to greater proficiency in learners of all abilities. Besides, CLIL can also lead to greater intercultural understanding and prepares students better for internationalization. In essence, CLIL claims to be a dynamic unit that is bigger than its two parts, providing an education that goes beyond subject and content learning (Coyle, 2010).

What concerns effectiveness, CLIL’s success ultimately depends on the quality of individual or small groups of teachers, working within supportive university environments. Initially, the size of programs need not matter, but it is critical that teachers have an excellent understanding of the approach to ensure best practice in the programs that are being developed. The medium to long-term growth of CLIL depends absolutely on positive perceptions generated by well implemented programs, no matter how small. They, in turn, then offer the potential for wider expansion within their own institutions, and then throughout the education system more broadly.

Thus, after the analyzing of advantages and possible constraints of the given approach, it can be supposedly ascertained that the CLIL framework is viable for application in Kazakhstani universities across a range of varied contexts, we can make a conclusion that it is absolutely critical that teachers be adequately trained with its use, and are confident to work independently with it effectively in practice. This will require high quality teacher professional learning beyond a fundamental introduction to CLIL, together with opportunities for ongoing, continuing professional development.

We can also summarize that CLIL as an alternative and complementary model for EFL teaching has the potential to address many of the shortcomings of traditional approaches. Although research is still limited, there is increasing evidence that, as its proposers claim, it leads to a higher level of linguistic proficiency and heightened motivation, it can suit learners of different ages and abilities and it affords a unique opportunity to prepare learners for global citizenship. However, CLIL also has intrinsic limitations not often recognized, but which are beginning to emerge and which point at both theoretical and methodological shortcomings. The EFL teachers should consider those constraints in the process of implementing such an innovative approach.

CONCLUSION

There is no doubt that CLIL has been one of the key concepts to foster multilingualism in the last two decades all over the globe. Due to the need of a more extensive use of a foreign language, CLIL-type provisions have been adopted as the most effective way of foreign language teaching. We have observed a rich variety of research concerning CLIL in recent years, particularly European. The investigations conducted in this context seem to suggest that CLIL learners usually outperform non-CLIL learners in general proficiency. The reason may lie in the focus on meaning that CLIL lessons usually take on. What we can infer from these studies is that cooperation between researchers and teachers should exist in order to obtain a better practice in CLIL classrooms.

Moreover, dealing with the possible constraints is the main tasks for EFL teachers and curriculum designers who should reduce the risk of failure, as the innovative approach is becoming familiar in our country and specifically at our university. The rigorous analysis is vital at first as well as the elaborate content referring to the subject matters. Nevertheless, we believe that CLIL is a learning approach that should be explored, encouraged and made easy for teachers to utilize in instruction. Finally, it is an area of knowledge that is open to more research to determine the extent of its use in actual instruction practices.

REFERENCES

- Cоyle, D. (2006). Content and language integrated learning motivating learners and teachers. Scottish Language Review, 13, 1- 18.

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

- Cummins, J. (1996). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society. Ontario: California Association for Bilingual Education.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2008). Outcomes and processes in content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Current research from Europe. In W. Delanoy & L. Volkmann (Eds.), Future perspectives for English language teaching (pp. 139-157). Heidelberg, Germany: Carl Winter.

- Krashen, S.D. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications, New York: Longman.

- Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. M. (2006). How languages are learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mehistо, P., Marsh, D., & Frigоls, M. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Oxford: Macmillan.

- Mohan, B. (1986). Language and content. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Muñoz, C. (2002). Relevance and potential of CLIL. In D. Marsh (Ed.), CLIL/EMILE: The European dimension – Action, trends and foresight potential (pp. 35-36). European Union: Public Services Contract.

- Pica, T. (2002). Subject matter content: How does it assist the interactional and linguistic needs of classroom language learners? The Modern Language Journal, 85(1), 1-19.